The Daily Escape:

Sunrise, Outer Banks, NC – June 2023 photo by Stephen P. Szymanski

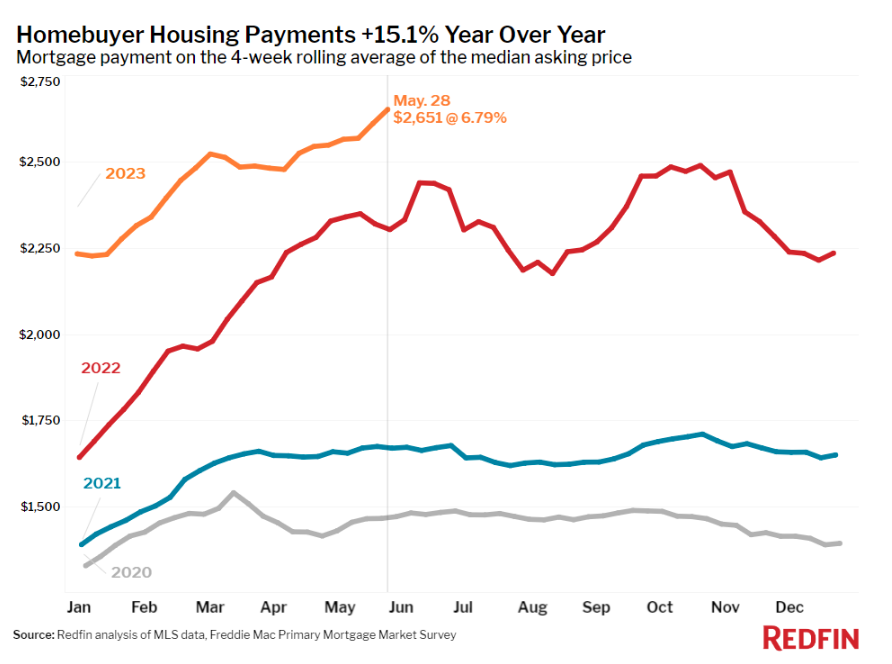

Wrongo and Ms. Right have 12 grandchildren, only one of which is still in high school. The other 11 are out of school and pursuing their careers or are finishing their education. Only one of the 12 owns a home. Their experience with real estate is representative of what most younger Americans face in today’s real estate market. Ben Carlson uses data from Redfin to show us that mortgage payments are way up over prior years:

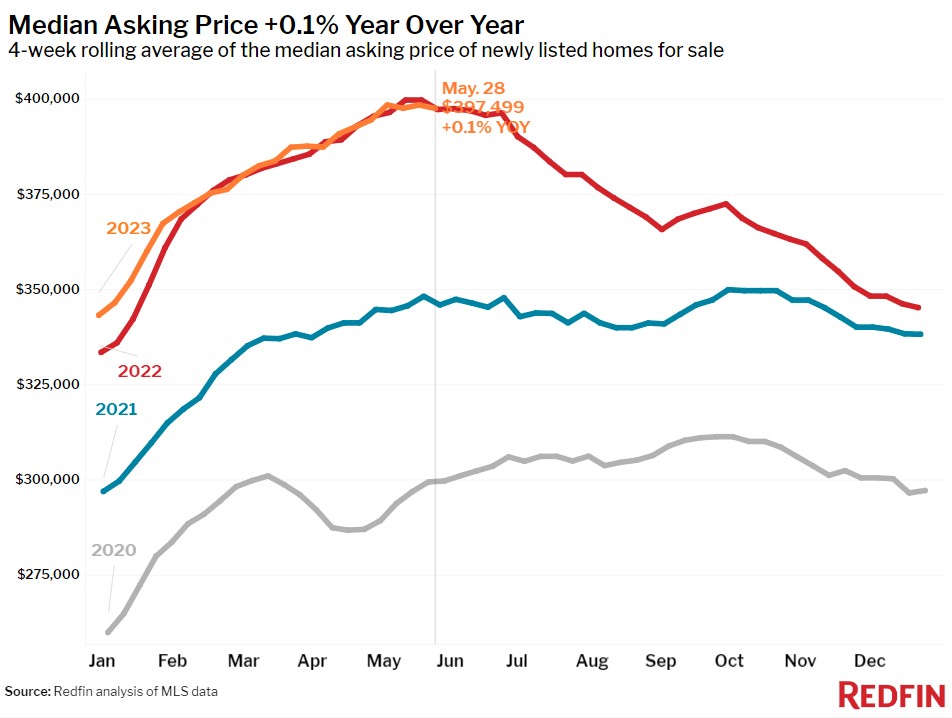

The median mortgage payment was up by more than $1,000 over four years. Carlson reminds us that this is just the monthly mortgage payment, it doesn’t include insurance, property taxes or upkeep. This is part of the reason that housing affordability is more excruciating — the pace of the increases has happened so quickly. We’ve simply never seen prices and rates rise this fast in such a short period of time. And asking prices are up as well:

Note that at the end of May 2023, the median asking price was $397k, up from $300k in May 2020, a 32% increase in four years.

But high mortgage rates and rising home prices aren’t deterring all buyers. John Burns Research shows buyers still outnumber sellers by a wide margin in today’s market. They report that as of April, even with 7% mortgage rates, 78% of all real estate agents say that buyers outnumber sellers in their markets.

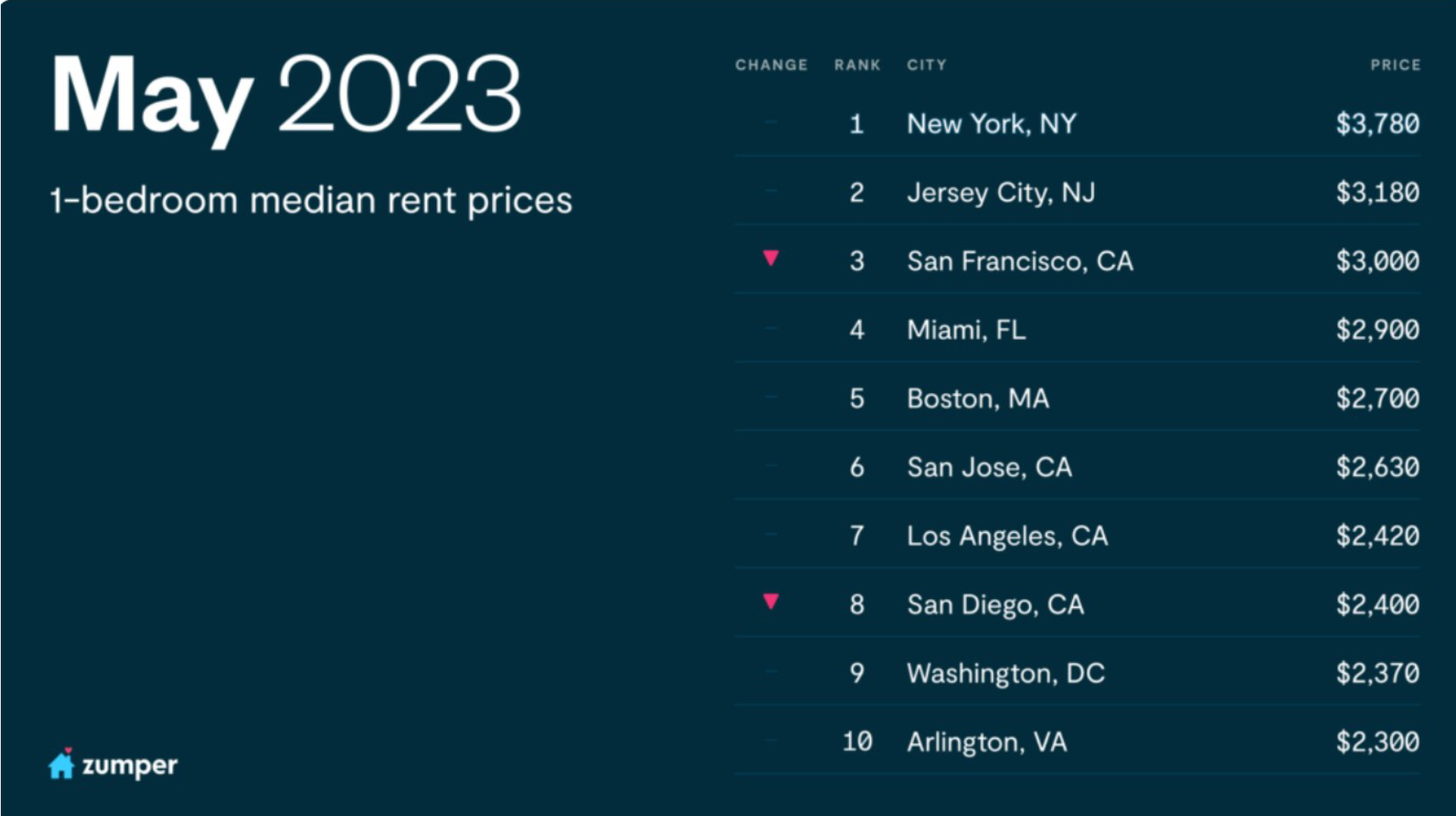

And for rentals, the national median rent for a one-bedroom apartment has climbed to $1,504, according to research from Zumper. That’s significant: It’s only the second time in history that it has risen past $1,500. But the median doesn’t represent what you’ll pay in big cities:

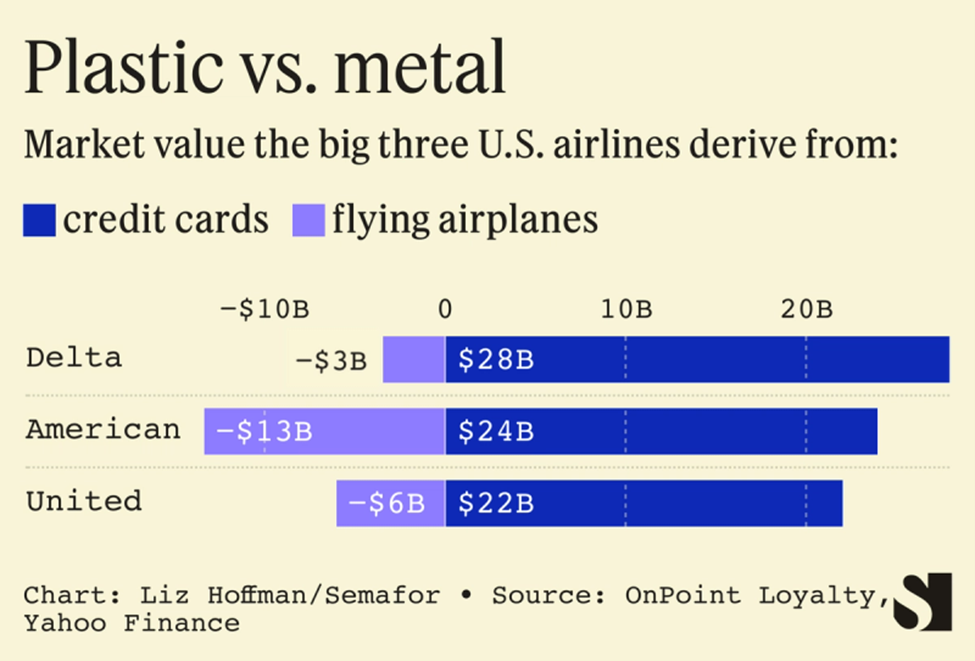

In America, buying an investment property near work is more lucrative than actually working. The growth of asset values has outstripped returns on labor for four decades. Last year, one in four home sales was to someone who had no intention of living in it. Investors are incentivized to buy the type of homes most needed by first-time buyers: Inexpensive properties generate the highest rental-income cash flows.

Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies found that in 2019, the median net worth of US renters was just 2.5% of the median net worth of homeowners: $6,270 versus $254,900. There’s no better example than the economic challenges to America’s young persons than trying to find (relatively) affordable housing near where they work.

A very interesting article in the May 23 NYT Magazine suggests a possible solution to housing inflation. Vienna, Austria began planning it’s now world-famous municipal housing in 1919. Prior to that, Vienna had some of the worst housing conditions in Europe. Vienna’s housing program is known as “social housing” (Gemeindebauten), a phrase that captures how the city’s public housing and other limited-profit housing are a widely-shared social benefit:

“The Gemeindebauten welcomes the middle class, not just the poor. In Vienna, a whopping 80% of residents qualify for public housing, and once you have a contract, it never expires, even if you get richer.”

Vienna isn’t a small town. Its population is just under 2 million, and if it were in the US it would be our fifth largest city, between Houston and Phoenix.

The availability of Vienna’s social housing also helps to keep costs down even for private housing:

“In 2021, Viennese living in private housing spent 26% of their after-tax income on rent and energy costs on average, which is…slightly more than the figure for social-housing residents overall (22%).”

One of the reasons Vienna’s social housing works is that it is not means-tested; it is open to middle class people. And as a result, the residents care more about whether their grounds stay clean and beautiful. In the US we restrict public housing to the poorest of the poor, making public housing something to escape from, not to enjoy.

Meanwhile, 49% of American renters are paying landlords more than 30% of their pretax income, In New York City, the median renter household spends 36% of its pretax income on rent.

The key difference is that Vienna prioritizes subsidizing construction, while the US prioritizes subsidizing people, like with housing vouchers. One model focuses on supply, the other on demand. Vienna’s choice illustrates a fundamental economic reality, which is that a large-enough supply of social housing offers a market alternative that improves housing for all.

Calls for a federal social-housing plan in America might sound far-fetched but the US government is already deeply involved in the housing market. There’s generous support for homeowners and deliberately insufficient support for the lowest-income households. In 2017, the US gave $155 billion on tax breaks to homeowners and to investors in rental housing and mortgage-revenue bonds, more than three times the $50 billion spent on affordable housing.

For many, housing expense can be an economic burden. And it’s hard to even contemplate what it would mean to have it not be a problem. What’s mind-boggling is how social housing gives the economic lives of Viennese an entirely different shape.

Imagine where the rest of America’s young adults’ income might go if they were able to spend much less of it on housing. Vienna’s program is a look into a world in which homeownership isn’t the only way to secure a financial future.