The Daily Escape:

Mt. Hood sunrise – February 2023 photo by Mitch Schreiber Photography

Happy Valentine’s Day for those who celebrate! If you don’t celebrate, find someone or something to give a little bit of love to.

In all of the hype about the Super Bowl and Rihanna’s halftime show, you may have missed that homes selling for less than $200k have basically disappeared in America.

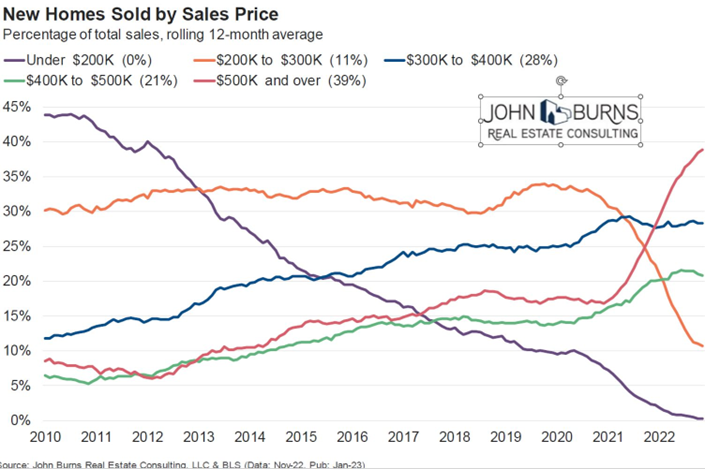

John Burns, a real estate consultant, reports that they are now 0% of the new home market. They were 40% of the market 10 years ago. Burns also says that $500k+ new homes have grown from 17% of the market to 38% of the market during Covid. He provides this handy chart showing how average home prices have changed since 2010:

At the same time, sales of homes going for $500k or more (red line) have shot up from less than 10% to nearly 40% of the new homes market and represent the largest share of new home sales.

This isn’t great for Millennials looking to buy their first homes, or for retirees who have to downsize. It also explains why many first-time homebuyers are angry.

It’s not only the $200k and under segment that has fallen off a cliff. New homes going for between $200k – $300k now make up just 11% of the total, down from 80% of all new home sales in the year 2000.

Ben Carlson shows Federal Reserve new home price data going back to 2000 that breaks down new homes price points more clearly. He says that those being sold for $750k and up have gone from less than 1% to more than 10% of the market.

A few reasons for the shifts: First, we’re not building enough new houses anymore. Second, we’ve seen changing tastes drive demand toward larger homes, helping move the market to a new floor in home prices. Inflation didn’t help either.

We overbuilt in the 2000s housing bubble, and that led to more than a decade of underbuilding ever since. There was a brief spike during the pandemic housing craze but that has abated with mortgage rates rising so rapidly in the past year.

In 2002-2006, we were building around 120,000 new homes per year. In 2022, it was more like 65,000 units per year. Tastes have changed as well. Houses today are substantially larger than they were in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

In his book The Fifties, David Halberstam talks about how the housing market played a huge role in the rise of the suburbs following World War II. Then houses were about 1,300 square feet. In the 1970s, the median size of a new home in the US was 1,525 square feet. Today it’s around 2,500 square feet.

Tastes have changed. People want bigger houses. They want open floor plans for entertaining, bigger bedrooms with more bathrooms, and more storage space for all of their stuff.

It’s also true that homebuilders aren’t incentivized to build starter homes anymore. In the 1950s the government helped out the troops and their families. With the GI Bill, the federal government took some of the risk that homebuilders wouldn’t be able to find mortgages for all the new houses they were building.

Local zoning regulations have made it difficult to get approvals to build new homes. So builders have moved upmarket in home size to justify those upfront expenses. Starter homes aren’t as profitable as they once were.

There’s a big change in the buyer’s market as well. The WSJ quotes John Burns: (emphasis by Wrongo)

“You now have permanent capital competing with a young couple trying to buy a house.” Burns estimates that in many of the nation’s top markets, roughly one in every five houses sold is bought by someone who never moves in.”

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in an article last week entitled: “American Dream For Rent: Investors elbow out individual home buyers. Metro Atlanta is ground zero for corporate purchases, locking families into renting’. The Journal says a generational housing shortage, inflated construction costs and a surge in consumer demand all contributed to the historic rise in prices.

But there’s little doubt that a flood of cash from institutional investors has exacerbated it. They quote Maura Neill, a realtor in Alpharetta:

“They go after every listing under $500,000…it’s like clockwork…The property gets listed and, sight unseen, they make offers within an hour.”

This is late-stage capitalism at work. Young working couples are increasingly shut out of buying homes. America is failing them. It would be helpful for families to build equity by purchasing homes instead of renting.

Pricing families out of home ownership carries risks to a cohesive society.

We should have a federal tax policy that disincentivizes ownership of multiple single-family homes, by investment funds. The way to remedy this is to steer investors to other assets that don’t directly impact individual welfare to the same degree as single family housing.