Americans worry that robots could make their jobs irrelevant. A new study shows that they may be correct. The report, Technology at Work v 2.0: The Future Is Not What It Used to Be, was conducted at University of Oxford in association with Citibank. Researchers Carl Frey and Mike Osborne, co-directors of the Oxford Martin Programme on Technology and Employment, found that 47% of US jobs are at risk of automation in the next two decades.

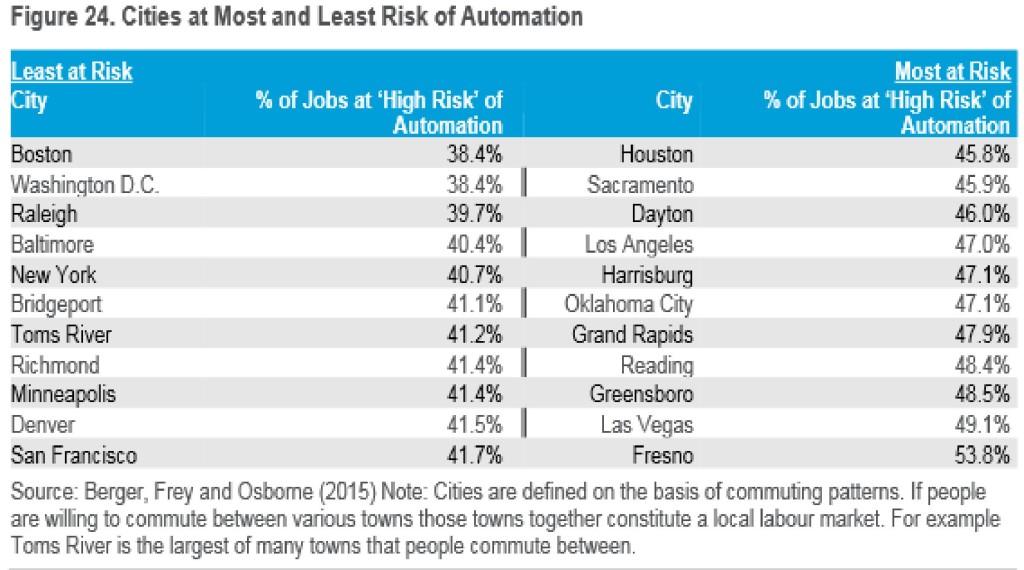

They also found that the city where you live may influence the risk of your work being automated. Among metro areas, Boston faces the lowest percentage of jobs likely to be automated, while Fresno, Calif., faces the highest. The cities that fared best in the survey have a cluster of skilled jobs, typically because they have developed a strong tech sector. Boston, for instance, which is home to a number of top universities and has many well educated residents, has become a global technology hub, transitioning successfully from its roots as a shipping center and manufacturing economy to a tech/finance center.

Here are the best/worst rankings:

Even in cities with the lowest percentage of jobs at risk of automation, nearly 40% of jobs could disappear because of technological innovation, the report finds. So how many workers are we talking about? The BLS reports that in December, 2015 our working population was 149.9 million; 40% of that number would be 60 million people unemployed in the next 20 years. Perhaps it won’t be that bad, maybe 20-30 million jobs will replace the approximately 60 million we stand to lose.

No politician will be able to paint a happy face on THAT.

Skeptics will say not to worry, that the economy has always adapted over time, and created new kinds of jobs. The classic example they use is agriculture. In the 1800s, 80% of the US labor force worked on farms. Today it’s 2%. Obviously, mechanization didn’t destroy the economy; it made it better. Food is now really cheap compared to what it used to cost, and as a result, people have money to spend on other things and they’ve transitioned to jobs in other areas.

But, the agricultural revolution was about specialized equipment that couldn’t be transferred to other industries. You couldn’t take farm machinery and have it flip hamburgers. Information technology is totally different. It’s a broad-based general purpose technology.

There just won’t be new jobs available for all these displaced workers.

There will certainly be many new industries, (think nanotechnology and synthetic biology), and those jobs will be highly paid. But they won’t employ many people. They’ll use lots of technology, rely on big computing centers, and be heavily automated.

Think about what Facebook and Twitter have added to the jobs economy: They are two of our very “best” success stories, and they only employ 8,100 workers. They have had a huge impact on society, and have created significant value for their owners, but the total jobs they have created are only a rounding error in the US economy.

Much of what we buy is produced in factories increasingly run with robots, and maintained and operated by small cadres of engineers. Also, keep in mind that globally, some 3 billion people are already looking for work and the vast majority are willing to work for less than the average American.

So, we can expect an ever-greater number of unemployed chasing an ever-shrinking number of jobs that can’t be eliminated or simplified by technology. Thus, the prognosis for many of our medium and some higher-skilled workers appears grim.

Incomes will continue to stagnate, because automation does not threaten unskilled jobs. This is sometimes called “Moravec’s Paradox”, which says that, contrary to traditional assumptions, high-level reasoning requires relatively little computation, but low-level sensorimotor skills require enormous computational resources. The “Roomba” robotic vacuum cleaner remains just an expensive toy. It has had zero impact on the market for janitors and maids like a rechargeable cordless sweeper has done, yet, wages for American janitors and maids have fallen because of competition from the currently unemployed and newly arrived immigrants.

If we forecast continuing technology breakthroughs (and we should), and combine that with the 3 billion people currently looking for work globally, we have to conclude that the planet is overpopulated if the goal is a growing global middle class.

This is why the quest for better technology has become the enemy of sustaining middle class job growth in the developed world.

I don’t see any reason to worry about finding new jobs for those displaced by automation. If the machines follow the script, they will kill most of the human population.

Have none of these inventors been watching movies over the last 30 years? Slow the role and stop making the machines smarter!