Our industrial heartland has withered away, in that there are fewer manufacturing jobs than ever, while manufacturing revenues have never been higher. Forty years of promises by politicians have come to nothing: These people are victims of a world order in which corporations have either exported or automated those jobs, with no responsibility to workers. It is left to the towns of Middle America and the federal government to clean up their mess.

This world order we live in today was born in 1980, with Thatcher and Reagan. According to Ian Welsh, the world order made a few core promises:

If the rich have more money, they will create more jobs.

Lower taxes will lead to more prosperity.

Increases in housing and stock market prices will increase prosperity for everyone.

Trade deals and globalization will make everyone better off.

Those promises were not kept, and in America’s Midwest, economic stress is now the order of the day. That stress has contributed to rising rates of drug addiction and falling life expectancy.

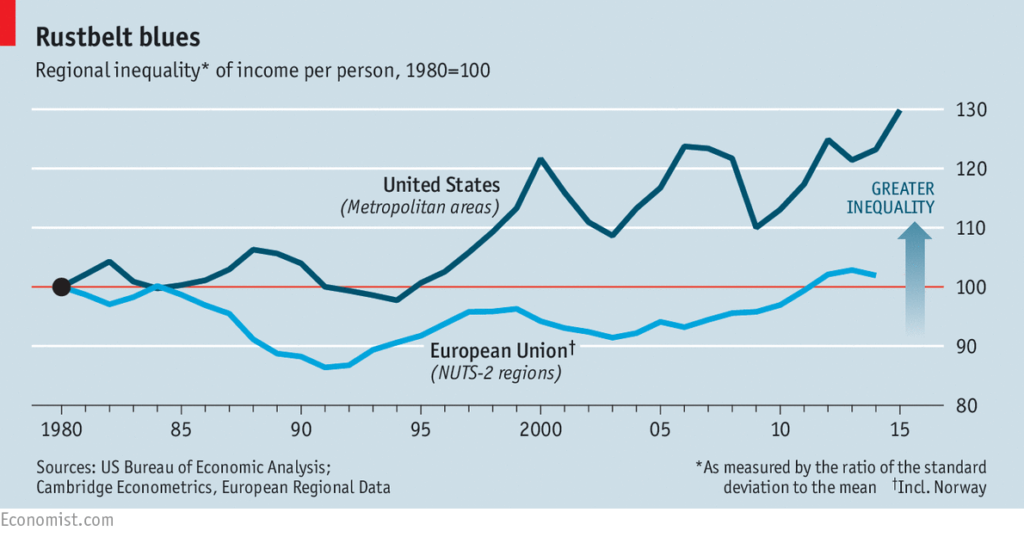

Understandably frustrated, Ohioans and other Midwesterners gave Donald Trump a victory in November. His win has refocused attention by pundits and pols on the plight of our failing de-industrialized areas. While we have economic growth, we also have growing inequality. Here is a graphic illustration of the problem, comparing the US with the EU:

The Economist reports that from 1880 to 1980, the incomes of poorer and richer American states tended to converge, at a rate of nearly 2% per year. The chart above shows that the pattern no longer exists. This causes us to ask if the shift of resources and people from places in decline to places that are growing is simply taking longer to adjust, or has the current world order failed our people? In econo-speak, the gains in some regions should compensate those regions and towns harmed by the shift, leaving everyone better off.

But that is a political and financial lie promulgated by the very corporations that benefited, and by their political and economist cheerleaders.

With economic decline, some towns and cities became poverty traps. A shrinking tax base means deterioration in local services (think Detroit). Public education that might provide the young with new skills and thus opportunities, fails. Those that remain are on government subsidies or hold low-wage service jobs, or both. It is impossible to tell these citizens that the decay of their home town is an acceptable cost of the rough-and-tumble of the global economy.

Politicians are short on solutions. Since housing costs have risen sharply in towns and cities that are growing, underemployed Americans are less likely to move, and those who do, are less likely to head for richer places. Enrico Moretti of the University of California, Berkeley and Chang-tai Hsieh of the University of Chicago argue that our GDP could be 13.5% higher if this wasn’t the situation in America.

But if moving isn’t an option, what can be done to improve the outlook for those who are left behind?

Would more government subsidies help? Prosperous tax payers already support poorer ones. Subsidies for health insurance costs with Obamacare, as well as industrial tax incentives provide some cushion, but they are not likely to deliver long-run economic recovery, and they have not stemmed the growth of populist political sentiment.

To be fair, many people in Ohio and elsewhere want good jobs, but without having to move too far to get them. That may be impossible.

In the 19th century, the federal government gave land to states, which they could sell to raise proceeds for “land-grant universities”. Those universities, including some that are among our finest, were given a practical task: to develop and disseminate new techniques in agriculture and engineering. They went on to become centers of advanced research and, in some cases, hubs of local innovation and economic growth.

Politicians and academic economists might disdain a modern-day version of the program, one that would train workers, foster new ideas, and strengthen weakened regional economies.

But if our politicians do not provide answers, our populist insurgents will.

Time for a Christmas song. Here is Elvis with “Santa Claus Is Back in Town & Blue Christmas”, from his comeback special on NBC. This was recorded over six days in June, 1968 and aired on December 1, 1968. Elvis flubs “Santa Claus is Back in Town”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WgLpMwkfOgw

Despite his flub, he does get this line right:

“You don’t see me comin in no big black Cadillac”

Kind of like out-of-work Ohioans.

I believe that we need to burden the outsourcing of jobs and the purchase of goods produced in part or in full by non US labor with a tariff. This would equalize the costs of services and goods produced in the US. We also need to retain and even grown the production of wood furniture – something that once provided excellent employment up and down the Appalachians. Not high tech, but decent jobs. A tariff would do that.