The Daily Escape:

Sunset in Yarmouth Port, Cape Cod, MA – July 2023 photo by Cynthia Maciaga

The semiconductor industry is big, complex, and important. Semiconductors are also an important test case for America’s ability to revive its domestic manufacturing base. There’s a lot riding on Biden’s Chips Act that became law one year ago. It is a $50 billion package of subsidies, tax credits and other sweeteners designed to bring advanced chipmaking back to America.

As a result, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) is investing $40 billion in Arizona. Samsung is investing $17 billion in Texas. Intel, America’s biggest chipmaker, will spend $40 billion on four semiconductor fabrication plants, or “fabs” in semiconductor parlance, in Arizona and Ohio. Both Democrats and Republicans regard it as a bipartisan legislative triumph.

But, finding highly skilled labor is key to the Act’s success. While America still has world-class semiconductor researchers and designers, we no longer have the kind of skilled labor that turns silicon wafers into electronic circuits. Chief Investment Officer magazine quotes Joseph Quinlan of Bank of America (BOA):

“America’s manufacturing renaissance could either be delayed or derailed by mounting structural headwinds….The US will have graduated only 108,000 technicians (who operate, maintain and fix electronic gear) by 2030, but demand is for 130,000 by then….Similarly, the nation will have produced 42,000 engineers and 21,000 computer scientists at that point, yet will need 69,000 and 34,000, respectively.”

BOA says that the other shortfall is construction workers. Construction of US factories has climbed 80% from a year ago, yet the nation has 374,000 unfilled construction jobs. We’re already seeing the problem. From the Economist:

“…The first of TSMC‘s factories was due to start production next year. But in July it announced that the launch would be put back to 2025 because it could not find enough workers with the expertise to install equipment at such a high-tech facility.”

The problem is during the delicate final phase of installing the most high-end equipment. Mark Liu, TSMC’s chair, said in a July earnings call:

“…there is an insufficient amount of skilled workers with those specialized expertise required for equipment installation in a semiconductor-grade facility.”

As a result, TSMC is sending skilled workers from Taiwan to teach Americans how to do the job. The Commerce Department forecasts that about 100,000 workers may be needed for the construction of these new fabs in the US.

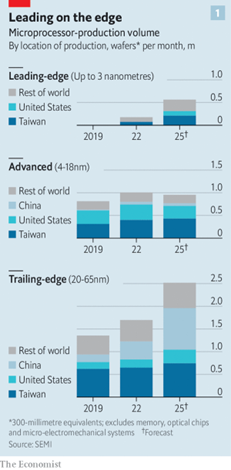

The chip market breaks down into “leading edge” chips, followed by “advanced” chips and “trailing edge” chips, sorted from the smallest chips to the largest. The Economist says that by 2025, American chip factories expect to be churning out 18% of the world’s leading-edge chips (see chart below):

This seems highly optimistic if we can’t get these new plants built or staff them. Leading-edge fabs that are built in America will take longer to build and will be smaller than those in Asia. In China and Taiwan, companies can build out a new fab in 650 days. In America, the average construction time is expected to be 900 days, or 40% longer. Construction costs, therefore, can be 40% more in America than in Asia.

Regarding size, in Arizona, TSMC plans to make 50,000 wafers a month—equivalent to two “mega-fabs”, as the company calls them. In Taiwan, TSMC operates four “giga-fabs”, each producing at least 100,000 wafers a month. Size matters: The more chips a fab makes, the lower the unit cost.

More from the Economist: (emphasis by Wrongo)

“America will produce enough cutting-edge chips to meet only about a third of domestic demand. Apple will keep sourcing high-end processors for its iPhones from Taiwan.”

Overcapacity is a possible threat. The Economist says that in 2019, China made one fifth of “trailing-edge” chips, which go into everything from washing machines to cars and aircraft. But by 2025 it will produce more than a third of them. It’s possible that excess supply from China will put downward pressure on prices. In the long run, this could hurt higher-cost American fabs.

So, while there has been substantial progress in just a year, the US isn’t going to undo 20+ years of offshoring chip manufacturing in the next 24 months. The Commerce Department says it wants companies to collaborate on building up a construction workforce, so that workers trained for one project can move on to other fabs that are being built. In this respect, TSMC’s plan to import Taiwanese trainers is less of a bug than a feature, part of the process of helping to build knowledge.

Once the fabs are built, they’ll need technicians to operate them. Such workers have historically required two years of training at a community college or a vocational school. But companies and educators are experimenting with much shorter courses. Columbus State Community College in Ohio, where Intel is building two fabs, is offering a one-year program. The aim is for students to be job ready for Intel as their fabs come online.

But, will these companies be willing to put candidates with one year’s training anywhere near the multi-million-dollar machinery inside their fabs?

The fabs also need engineers to run them. Universities near some of the fabs under construction, including Arizona State and Ohio State, have expanded their offerings of semiconductor courses as part of degrees in engineering and physical sciences. Leading the charge is Purdue University in Indiana: last year it launched a semiconductor degree program for both undergraduates and graduates.

And the flow of students seems encouraging. Intel expected 100 registrants for its quick-start courses, but 900 showed up. At Purdue enrollment has also been very strong. Handshake, a job platform for recent graduates, reported that applications for full-time jobs at semiconductor companies were up by 79% compared with last year, versus 19% in other sectors.

Returning to having a strong, vibrant high tech manufacturing industry in the US is good, both strategically and economically. But for the immediate future, it remains a gamble: We’re saying that the economic reasoning for moving manufacturing offshore in the past still exists. But it’s important enough strategically that we (and these profit-seeking corporations) will somehow underwrite the cost disadvantages.

Relearning basic skills such as cutting wafers into chips and packaging them in hard plastic casings will take time. The welcome news for these new fabs is that colleges and universities see an opportunity in helping train the new labor force.

But we will still be dependent on other countries. We do not have a secure domestic supply of lithium, nickel, graphite and other minerals needed to expand production of solar panels, wind turbines, semiconductors and electric vehicles. BOA points out that American imports of lithium-ion batteries from China more than doubled in 2022, to $9 billion.

So, while there’s lots going on that may someday be positive, China represents a potentially dangerous choke point given that US-Sino bilateral relations are at a decade’s low. We’re depending on them to continue providing much of the materials crucial to our new manufacturing capacity, while we’re in the middle of a serious rift with them.

Reshoring manufacturing, especially high value manufacturing is America’s dream. But it will take unprecedented cooperation between the government, multinational firms and our higher education system to make it happen.

Decades ago, Kodak was in trouble – not sure if late 70s or early 80s. But they wanted to invest in building a digital camera. They could design one, but the learned that there was no shutter capacity in the US. Shutters are still mechanical. Also no lens building capacity (for lenses for cameras). In any case Kodak’s long run ended. This is different because at least some in the US care. But we must remember that there may be hiccups.

New and advanced technology require persistence. An example of what happens is with wind power. Costs are going up and projects are being stalled or cancelled. In NJ the governor was faced with a cost problem so is giving the maker a grant to keep the project going But in the NJ state legislature Republicans are calling this a bailout and want to put a stop to it.

In fact there will always be cost overruns etc with any new and complex tech. Sometimes the project will fail. But giving up is just that, giving up.

One of the legislators who wants to pull the plug is from my local district. Nice guy but an attorney and a person who clearly has never worked at a real job. He replaced his father when his father retired.

Re: ” … it will take unprecedented cooperation between the government, multinational firms and our higher education system to make it happen.”

For starters, stop gov’t funding for majors in college that have little chance of leading to a decent job in those fields.