(You may have noticed our sporadic blogging. Wrongo is nearing the end of a year-long project that will be operational in Chicago during the week of August 9-15. During these days leading up to the project’s start, it has been all conference calls and negotiations with 3rd parties. Regular blogging will return during the week of 8/16.)

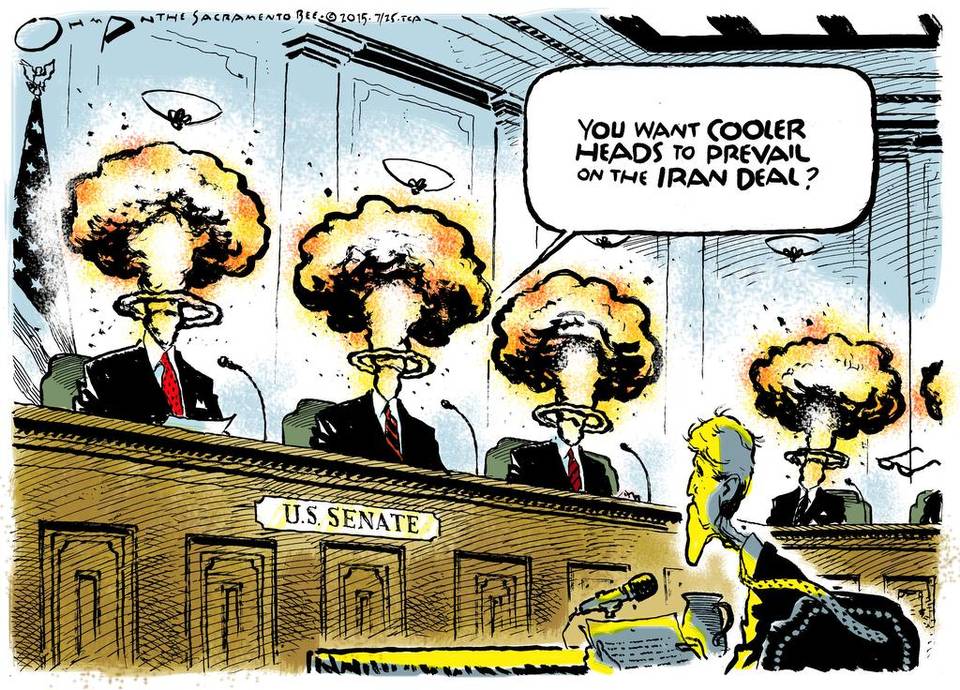

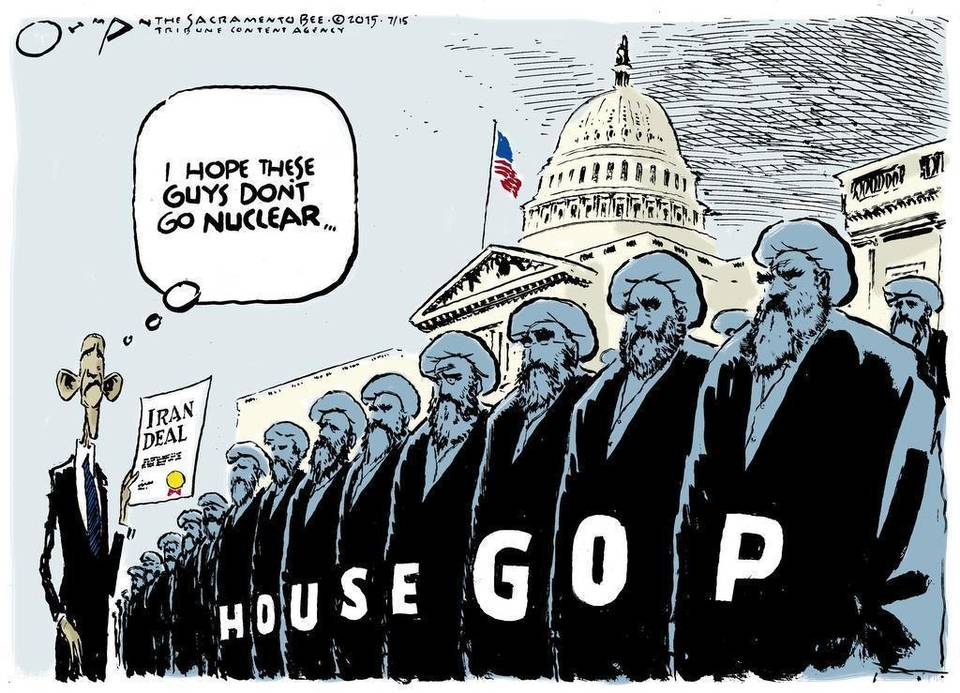

Let’s look at the one part of the American summer that is seeing rapid growth, that of rampant Dickitude. We start with Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) saying about the Iran deal:

If this deal goes through, the Obama administration will become the leading financier of terrorism against America in the world…I’ve heard this referred to before as the ‘Jihadist Stimulus Bill’.

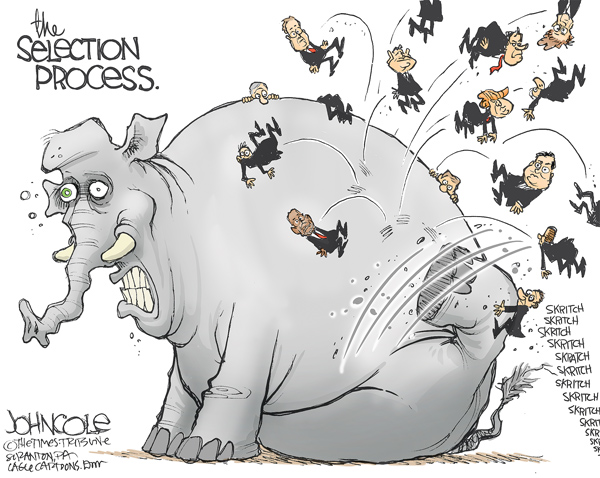

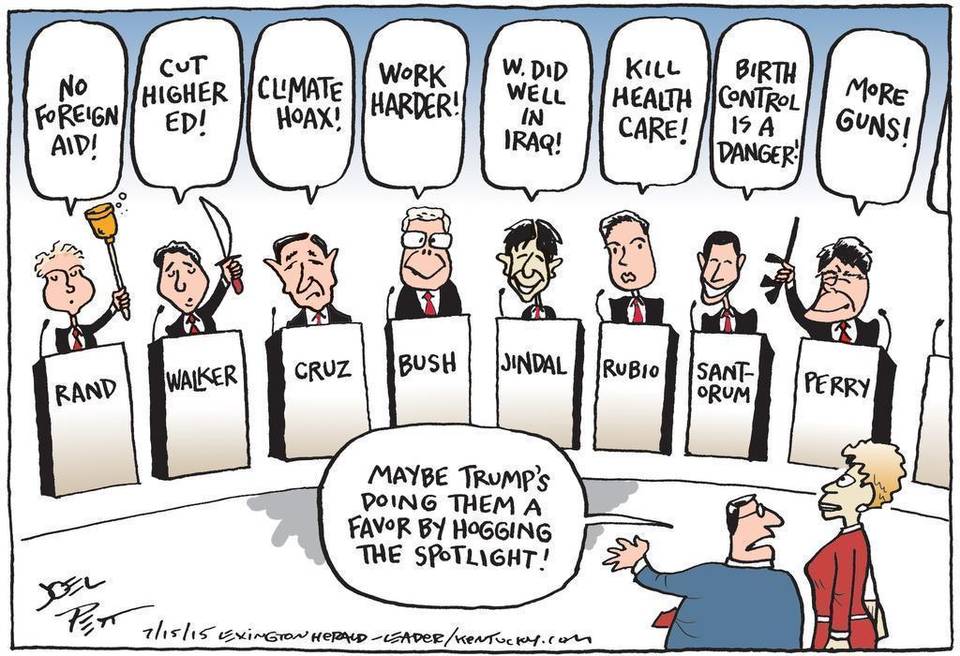

Expect full blown, uncensored, nuclear Republican crazy until after the Fox debate.

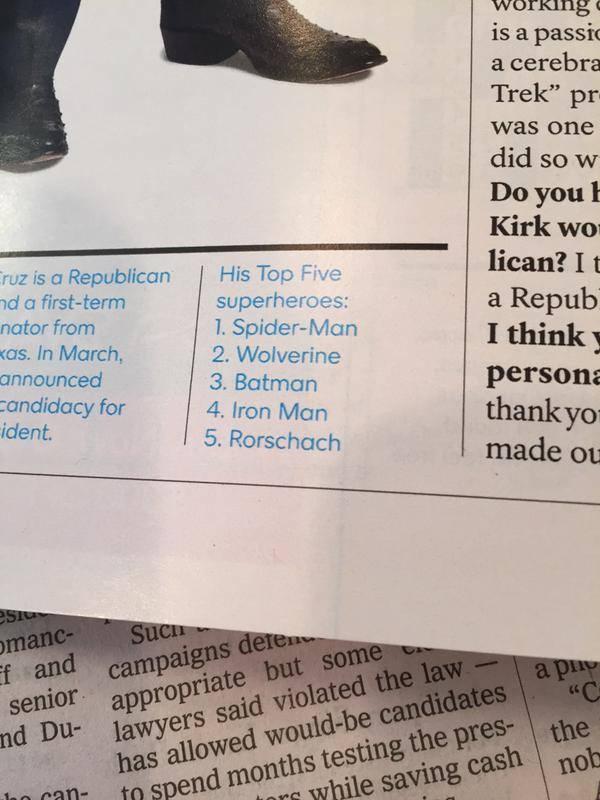

You probably didn’t know that Ted Cruz is a sci-fi/comic book fan, a fact highlighted in an interview published last week by The New York Times Magazine. Mr. Cruz told Fox News that his top 5 superheroes are: (see below from a tweet by Andreu Aitch)

Rorschach, who you may not know, is one of the main characters of Alan Moore’s Watchmen. Rorschach is a man who gives lip service to living by a morally unassailable, black and white code, but who nevertheless picks and chooses much of what he considers to be right and wrong entirely based on his own prejudices. Rorschach is the kind of person who murders people for the “greater good”.

Rorschach’s epitaph is:

Never compromise, not even in the face of Armageddon.

Doesn’t that seem like Cruz’s philosophy, where he’s willing to publicly fight his party’s leadership and shut down the federal government in order to spare his country from the impact of Obamacare? You might find a guy with a philosophy that prioritizes principle over peace, even though it might bring nuclear war, to be a risky person as your president.

BTW, why do our newsies want us to pick our president based on what cartoon character he likes best?

Speaking of Dickitude, what about Walter Palmer, the lion-killing dentist? The unauthorized killing of Cecil the lion in Zimbabwe, apparently was a poaching. This recalls that Palmer pleaded guilty in 2008 to the poaching of a black bear in Wisconsin, so Palmer is a serial poacher. And, in 2009, Palmer agreed to a settlement with the Minnesota Board of Dentistry over allegations that he sexually harassed a receptionist. Without admitting guilt, Palmer settled and paid $127,500 to the woman, who also was his patient.

Let’s hope he does time in Zimbabwe.

Moving on, The Hill reports that Federal prosecutors charged Rep. Chaka Fattah, (D-Pa), Wednesday in a 29-count indictment with racketeering, conspiracy, bribery and wire fraud. The FBI and IRS launched its probe of the Congressman’s activities in March 2013. The indictment alleges that, in connection with his failed mayoral bid in 2007, Fattah and his associates borrowed $1 million from a wealthy supporter and disguised the funds as a loan to a consulting company. He then created sham contracts and made false accounting records, tax returns and campaign finance disclosure statements.

In another alleged scheme, beginning in 2008, Fattah lobbied individuals in the executive branch in an effort to secure an ambassadorship or an appointment to the US Trade Commission for 69-year-old lobbyist Herbert Vederman, for which Vederman paid Fattah an $18,000 bribe.

Want to bet he is re-elected?

Finally, Rick Perry said in an interview on CNN’s “State of the Union” that the shooting in Lafayette, Louisiana show that gun-free zones are “a bad idea”. He said he believes people should be able to take their firearms to the movies:

I think that you allow the citizens of this country, who [are] appropriately trained, appropriately backgrounded, know how to handle and use firearms, to carry them. I believe that, with all my heart, that if you have the citizens who are well trained, and particularly in these places that are considered to be gun-free zones, that we can stop that type of activity, or stop it before there’s as many people that are impacted as what we saw in Lafayette.

Imagine adding guns to a dark, loud environment. What could possibly go wrong? Especially if some sort of escalation were to occur, and a group of true heroes packing handguns are there to intervene. Hundreds of people in a dark theater shooting at the same time to “defend” themselves.

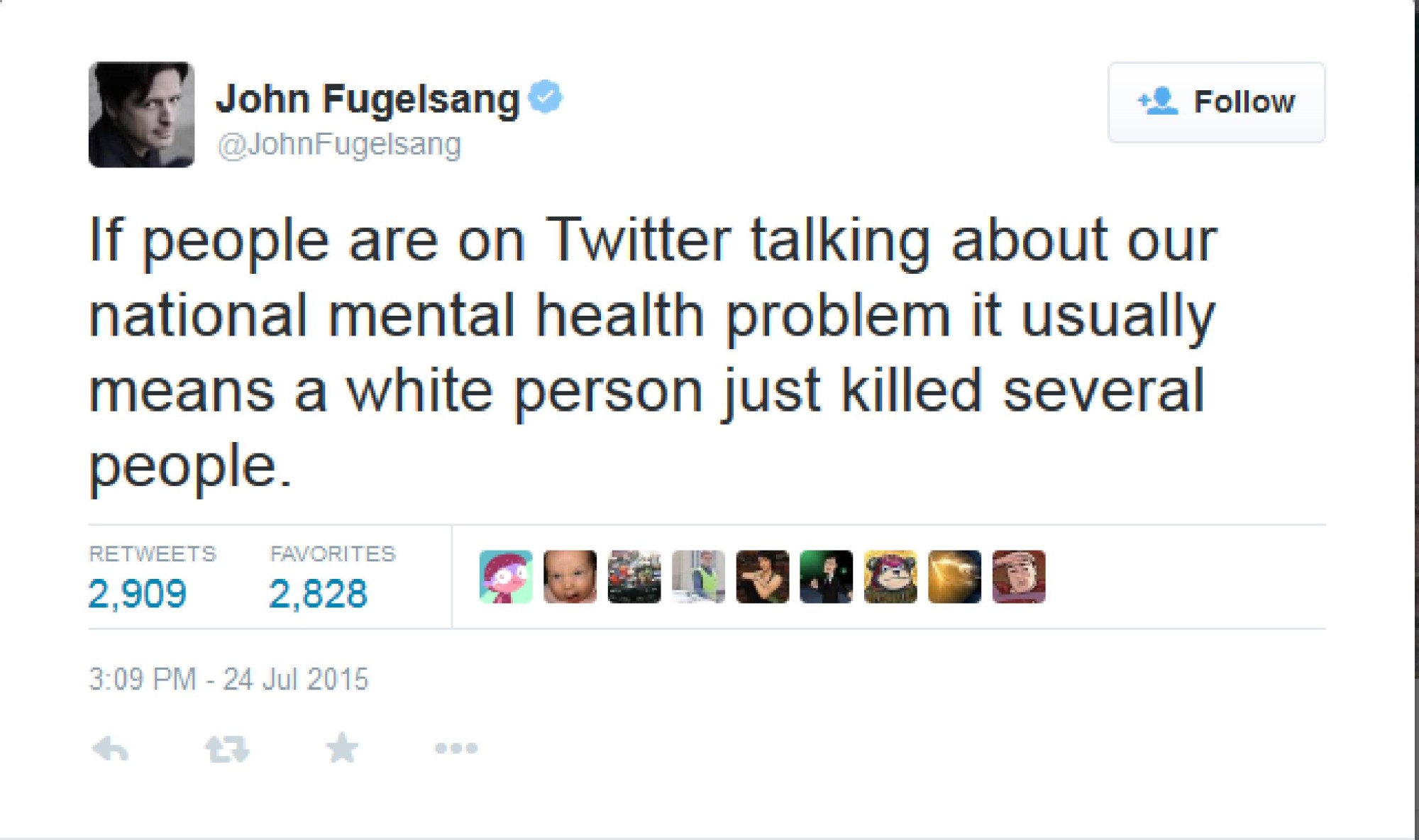

OTOH, we have zero interest in actually dealing with the problem: