Yesterday, Wrongo broke the bad news about the May job report. Exactly one year ago, Wrongo wrote “Technology Isn’t Creating Enough Middle Class Jobs.” That article spoke about how deploying new technologies continues to cost more and more mid-skilled jobs.

With low interest rates, the cost of capital investments have fallen relative to the cost of labor, and businesses have rushed to replace workers with technology. Because of technology, since the mid-1970s capital and labor have become more substitutable, and it’s a major global trend. Some proof of this is in the article in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, where Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman from the University of Chicago found that the share of income going to workers has been declining around the world.

As Brad Delong, economist at the University of California, Berkeley, wrote recently, throughout most of human history, every new machine that took the job once performed by a person’s hands and muscles increased the demand for complementary human skills — like those performed by eyes, ears or brains.

This is no longer true. From Wrongo’s June, 2015 column:

Facebook is touted as a prime player in the knowledge economy, but it only employs 5,800 to service 1 billion customers! Twitter has 400 million total users. It has 2,300 employees.

What is the value of Facebook and Twitter to the jobs economy? These are two of our very “best” success stories, and they only employ 8,100 workers.

These firms have had a huge impact on society, but the total jobs they have created are only a rounding error in our economy.

As the idea sinks in that human workers may be less necessary than in the past, what happens if the job market stops providing a living wage for millions of Americans?

How will people afford to pay the rent? What will happen if the bottom quartile of workers in the US simply can’t find a job at a wage that could cover the cost of basic staples?

What if smart machines took out the lawyers and bankers? Bloomberg is reporting that job loss is on the way for bankers. Banks are racing to remake themselves as digital companies to cut costs. In other words, they’re preparing for the day that machines take over more of what used to be the sole province of humans: knowledge work. From Bloomberg:

State Street had 32,356 people on the payroll last year. About one of every five will be automated out of a job by 2020, according to Rogers. What the bank is doing presages broader changes about to sweep across the industry. A report in March by Citigroup…said that more than 1.8 million US and European bank workers could lose their jobs within 10 years.

They close by saying that Wall Street will go on—but without as many suits.

Some estimates say that automation could cost half of all current jobs in the next 20 years. The OECD thinks the number is smaller. They argued last month that lots of tasks were hard to automate, like face-to-face interaction with customers. They concluded that only 9% of American workers faced a high risk of being replaced by an automaton.

9% of today’s American workforce equals 13.6 million jobs. It just took us seven years to gain 14.5 million jobs, most of which were contractors and temp jobs.

The prognosis for many medium and some higher-skilled workers appears grim.

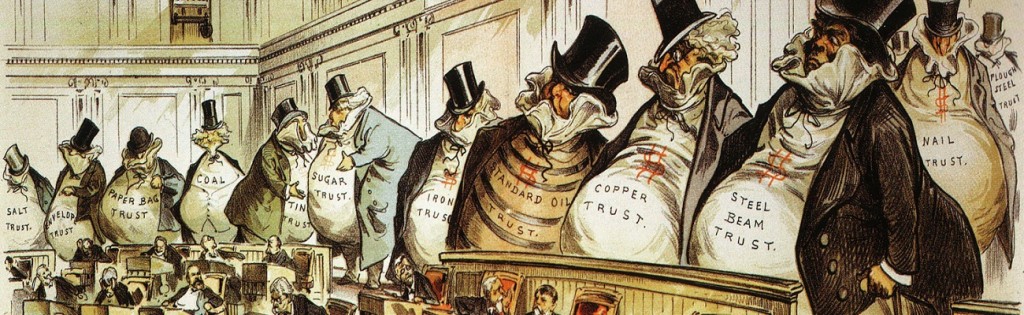

The corporatists have seen these forecasts. It explains their unwillingness to do anything serious to create effective jobs programs here at home. They don’t need to do anything, because there is a (virtually) infinite supply of skilled and unskilled workers in the overpopulated third world.

So, these are today’s questions for the Pant Suit and the Pant Load, and their answers need to be specific:

- Where will the household’s income come from when jobs alone can’t provide it?

- How will we deal with large-scale inequality that requires large-scale redistribution?

- Is it time to think about how to provide more income that isn’t directly tied to a job?

From Eduardo Porter:

For large categories of workers, wages are already inadequate. Many are withdrawing from the labor force altogether. In the 1960s, one in 20 men between 25 and 54 were not working. Today it’s three in 20. Although the population is generally healthier than it was in the 1960s; work is almost uniformly less demanding. Still, more workers are on disability.

The issue is not technology, or robots, or restoring our manufacturing base. It isn’t better skills, or technology or outsourcing. We have too many people chasing too few good jobs.

This is why we need the presidential candidates to speak the truth about job creation in America.