(This is the third column about US foreign policy. The other two columns are here and here.)

The past two columns have argued that our foreign policy does not employ any non-military strategies in areas where we compete with other nations or where there is local or regional conflict.

We have an insular view of our competition. We tend to see Vladimir Putin as a military strategist, massing his troops on the border of Ukraine, rolling over Crimea, providing the missiles to shoot down civilian airliners. Some, or all of that may be true, but Mr. Putin is a busy man who also uses soft power and commercial power. China, our great Asian competitor, follows a similar strategy to Russia’s.

We could learn a lot from our competitors. Last week saw Russia and China making soft power and commercial initiatives in South America. The Economist reports that Brazil’s President Rousseff hosted Mr. Putin, and China’s Xi Jinping as part of a summit of the BRICS group of emerging countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa).

While in South America, Mr. Putin also visited Cuba where he announced plans to re-open an intelligence base. Russia also agreed to write off 90% of Cuba’s $35 billion Soviet-era debt. Putin then went on to pitch the export of Russian nuclear technology to Argentina and a $1 billion anti-aircraft missile defense system to Brazil.

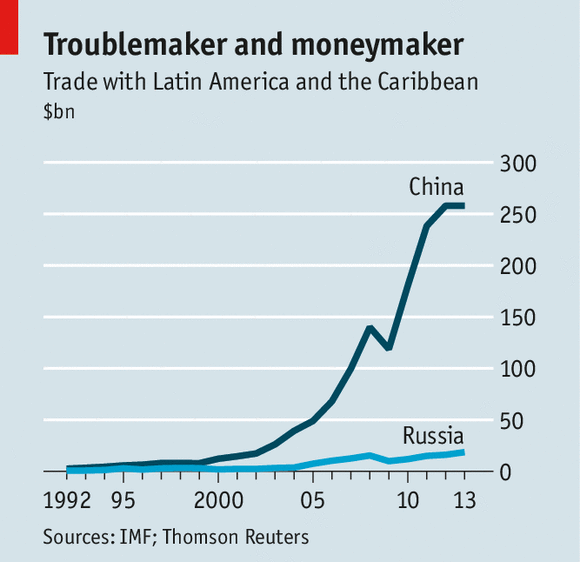

Mr. Xi met with the leaders of CELAC, a club of all 33 Latin American and Caribbean countries. In Venezuela he met with officials regarding China’s $50 billion in oil-backed loans. Chinese trade with the region has grown more than 20-fold in this century:

China has become a big investor, trading partner and lender in the region. While Latin America’s ties with China are far more recent than those with Russia, they are also much more important. Russia, which had made major inroads into Latin America in the 1960’s and 1970’s is now playing catch-up in many countries, and is closest to Venezuela.

By contrast, the US has a history of attempted and successful overthrows of governments, and meddling that have kept South America suspicious of our motives for decades. We have diplomatic problems with Brazil stemming from the NSA’s tapping of Ms. Rousseff’s personal mobile phone. We are deeply involved in a debt default to private US hedge fund lenders by Argentina, which was heard by our Supreme Court, who found in favor of the lenders not the country. We continue to view Cuba through a Soviet-era lens. The region no longer looks only to the United States and Europe.

While the BRICS countries were in Brazil, they agreed to establish a New Development Bank (NDB) at their summit meeting. The NDB will have a president (an Indian for the first six years), a Board of Governors Chair (a Russian), a Board of Directors Chair (a Brazilian), and a headquarters (in Shanghai). They also created a $100 billion Contingency Reserve Arrangement (CRA), meant to provide additional liquidity protection to member countries during balance of payments problems.

The BRICS wanted a vehicle that matches their rising economic strength, and they wanted a bigger voice than they have in the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Although the BRICS are one-fifth of the global economy, they are just 11% of the votes at the IMF. The BRICS bank/CRA could challenge World Bank-IMF hegemony. The new bank’s partners already lend more than the World Bank, which made $52 billion in loans last year, while China made loans of $240 billion and Brazil made $88 billion.

The WaPo Monkey Cage reported that Mr. Putin extolled the NDB and CRA as a way to prevent the “harassment” of countries whose foreign policy clashes with America or Europe (like his annexation of Crimea, perhaps?). They also observed that Mr. Xi Jinping sees a geopolitical role for the BRICS as part of his push to set up a new alternative to US ‘hegemony’. Mr. Xi has a vision of China as a leader of the non-aligned nations, a concept first developed in the 1950s. He says this despite taking an increasingly militarized stance on disputed maritime borders in Asia.

Taking a step back, China and Russia are seeking economic dominance of huge swaths of the world, while the US is trying to maintain its current dominance of the same swaths.

And one way China and Russia attempt to do this is through trade, investment and lending, while the US uses military and currency dominance. One major issue in the next decade or two will be whether the dollar can remain the world’s reserve currency. Although at this moment there is no contender in sight, the BRICS’ NDB and CRA could be the first step in China and Russia’s grand plan.

How we respond with soft power, how well we solve our domestic economic problems will go very far towards determining whether the US can blunt the geopolitical challenges from China and Russia.

Guns ain’t gonna get it done.

The US has a lot of “soft power” right now. But we also have the burden of being more or less on top. After all the global institutions of trade and order are of Western design and even if they don’t function well, they remain exporters of our ideas. And the IMF is in essence ours.

Russia has little but arms energy and old military technology. China is a far more serious competitor, but even with China, our leverage against them should be our own markets. But we don’t have the political will to abandon free trade and resume a regime of tariffs and trade quotas to keep our preserves (high tech, high value).

@ Terry: Agree with your assessment. our politics is our greatest problem. We are on the cusp of major global change, with new global powers, like China, Brazil and India that pose different problems, mostly economic. These are entirely different from what we faced in the cold war. We are also facing demographic change at home, which could make our politics more like Europe’s. The old, mostly white conservatives see what is coming, and they know it means they will lose power and control over our politics. They aren’t taking it lying down. How we get to a new consensus before we lose our global mojo, is our greatest challenge.