The Daily Escape:

Sunrise, with Mt. Hood in background, Vancouver, WA – November 2022 photo by Sanman Photography

The NYT has an article showing how the US tolerates a high number of auto-related deaths:

“The US has diverged over the past decade from other comparably developed countries, where traffic fatalities have been falling….In 2020, as car travel plummeted around the world, traffic fatalities broadly fell as well. But in the US, the opposite happened. Travel declined, and deaths still went up. Preliminary federal data suggests road fatalities rose again in 2021.”

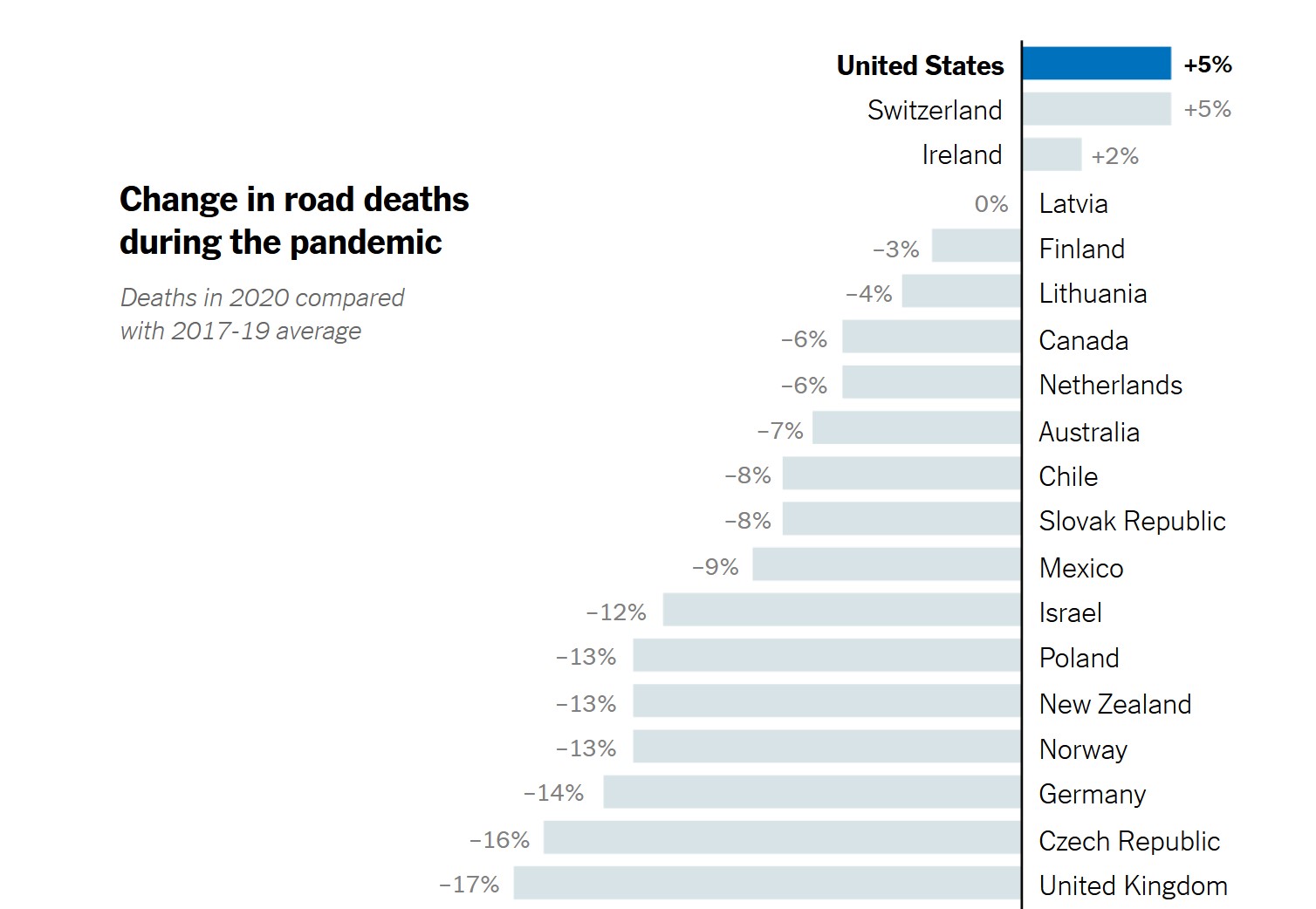

They helpfully include a chart that shows America’s relative ranking vs. other developed countries since the start of the pandemic in 2020:

(chart is truncated for viewing purposes)

More from the NYT:

“Safety advocates and government officials lament that so many deaths are…tolerated in America as an unavoidable cost of mass mobility. But…Americans die….in rising numbers even as roads around the world grow safer.”

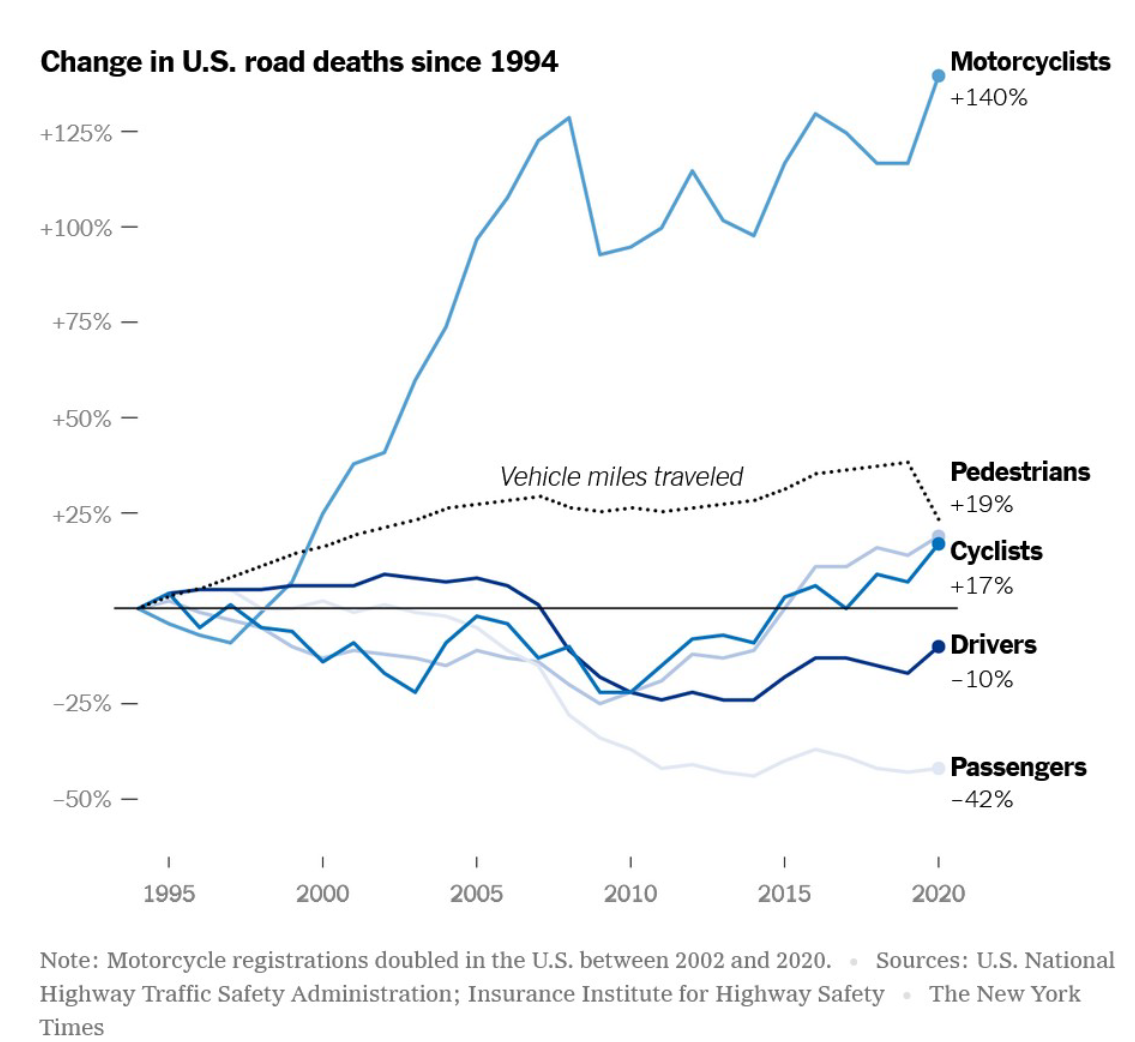

In 2021, nearly 43,000 people died on American roads. The recent rise in fatalities has been highest among those the government classifies as most vulnerable — cyclists, motorcyclists, pedestrians, even though miles traveled have fallen:

The NYT says that the explanation for America’s road safety record lies with a transportation system designed to move cars quickly, not to move people safely. They quote Jennifer Homendy, chair of the National Transportation Safety Board:

“Motor vehicles are first, highways are first, and everything else is an afterthought…”

To fix this means we must solve both infrastructural and cultural problems at the same time.

This year in our northwestern Connecticut town, we’re seeing an average of 3 accidents per day compared with 2.2 per day last year. Our population is growing, but certainly not as fast as our accident rate.

The explanation for the increases both locally and nationally isn’t simple to explain.

- Vehicles have grown significantly bigger and thus deadlier when they hit people.

- Some states curb the ability of local governments to set lower speed limits.

- The five-star federal safety rating that consumers can look for when buying a car today doesn’t take into consideration what that car might do to pedestrians.

- As cars grew safer for the people inside of them, we didn’t prioritize the safety of people outside of them.

The average car sold in the US is larger, taller, and heavier than in other developed countries. Many of these SUVs and trucks can weigh up to 9,000 pounds, like the latest Rivian and the electric Hummer. Their batteries alone weigh 3,000 pounds, the weight of the average car in the 1990s!

The larger size offsets the advancements in safety technology. Add in growing distracted driving: texting, work calls, difficult to navigate infotainment systems that lack physical buttons. And deaths are up in America.

In the 1990s, per capita roadway fatalities across developed countries were significantly higher than they are today. Back then, the US had fewer than South Korea, New Zealand, and Belgium. But other countries started to take pedestrian and cyclist injuries seriously in the 2000s. They made them a priority in both vehicle design and street design in a way that the US has never committed to.

In America, we prioritize straighter, smoother roads. We prioritize traveling long distances by car as fast as possible. Our culture and our infrastructure are designed to allow us to go faster on better roads. That has made us number one in road vehicle-caused deaths since the pandemic.

More American Exceptionalism! And given our exceptionalism in firearm fatalities, it’s hard to see how or why Americans would be willing to stop being exceptional in vehicle deaths either.

Biden’s infrastructure bill, passed last year, takes baby steps toward changing this. There’s more federal money for pedestrian and cycling infrastructure. And states are now required to analyze fatalities and serious injuries among “vulnerable road users” (people outside of cars) to identify the most dangerous traffic corridors and the potential ways to fix them.

States where vulnerable road users make up at least 15% of fatalities must spend at least 15% of their federal safety funds on improvements prioritizing those vulnerable users. Today, 32 states, plus Puerto Rico and DC, will have to meet this mandate.

Here in our CT town, Wrongo serves on the Municipal Roads Committee. We talk endlessly about how, once a road is repaired, speeds immediately go up. It took several years and much public disagreement to build a roundabout as a traffic calming measure on one accident-prone road.

In Europe, you see plenty of “traffic calming” measures. Chicanes, roundabouts, and narrower lanes bring vehicle-pedestrian fatalities down, in part by making drivers pay more attention. Therefore, driving becomes a bit more nerve-wracking, and people go slower.

Making that happen here would require Americans and politicians to buy into the idea that streets aren’t exclusively for cars.