This is not a column about Ferguson, except by extension. In August, after Ferguson, the images of cops climbing out of armored vehicles with military-grade weapons caused some in both Houses of Congress to push for change in the program. Lawmakers vowed changes to the 1033 Pentagon program that provides military-grade equipment to local police. The Obama administration called for a policy review of the 1033 program, but on Monday, they backed away from substantive changes to the program.

There was a White House meeting on Monday to address the issues raised by military-style policing and Ferguson. Yet, the evidence shows that the meeting has changed nothing. This was The Guardian’s Monday headline:

Obama resists demands to curtail police militarization calling instead for improved officer training

Mr. Obama did call for a $263m, three-year spending which, if approved by Congress, could lead to the purchase of 50,000 lapel-mounted cameras to record police officers on the job.

Sounds good, but there are 765,000 state & local law enforcement officers in America, so you better hope that you are stopped by one of the 6.3% of local police officers that will have a federally-funded camera three years from now. Oh, and hope that the digital file of your brush with the law hasn’t been accidentally erased.

The Institute for Public Accuracy made comments from Peter Kraska available. Kraska is considered a leading expert on police militarization. He said yesterday: (emphasis by the Wrongologist)

From my meeting at the White House, frankly, they — like most political players — were interested in a quick fix. They want to hear that by somehow tweaking the 1033 program (which transfers equipment from the Pentagon to local law enforcement) that they can have an impact. That program is important symbolically, but there’s an entire for-profit police militarization industry that wouldn’t be affected.

We also have to review the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) grant program which provides far more to local police than does the DOD. DHS grants are lucrative enough that many defense contractors are now turning their attention to police agencies — and some new companies focus solely on selling military-grade weaponry to police agencies who get those grants.

That means we’re now building a new industry whose sole function is to militarize domestic police departments. Which means it won’t be long before we see pro-militarization lobbying and pressure groups with lots of (mostly taxpayer) money to spend to fight just the reforms the Obama administration and some in Congress say are necessary.

Say hello to the military/police/industrial complex.

And why have we entered a time of “shoot first” in our cities? It must be because our police feel that their lives are more in danger than ever. Sorry, that isn’t supported by the facts: The number of law enforcement officers killed as a result of criminal acts:

2004: 57

2009: 48

2012: 49

2013: 27

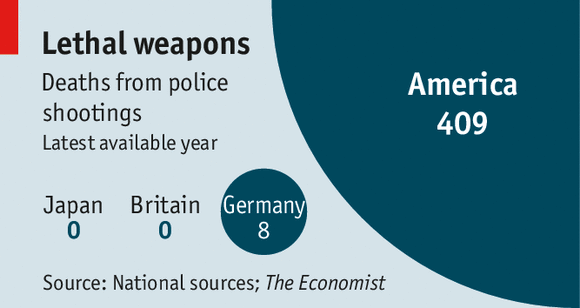

So, if there are 765k in local law enforcement that equates to a 2013 death rate from criminals of 3 per hundred thousand per year. Also, 2013 incidents are equal to the lowest level since 1887. Yet, nationwide, America’s police kill roughly one person a day:

The Economist, August 2014

And evidence exists that this number is dramatically understated. The FB page, Killed by Police says the number of deaths at the hands of police as reported to them since their launch in May 2013, is 1450. In 1994, Congress instructed the DOJ to “acquire data about the use of excessive force by law enforcement officers” and “publish an annual summary”. They have yet to do that. There are over 17,000 law enforcement agencies in the country, yet fewer than 900 report their shootings to the FBI.

Radley Balko in The WaPo concludes that militarization of police and their use of military-style force to suppress protests are bad mistakes. He quotes the Salt Lake City chief of police, Chris Burbank:

I just don’t like the riot gear…Some say not using it exposes my officers to a little bit more risk. That could be, but risk is part of the job. I’m just convinced that when we don riot gear, it says ‘throw rocks and bottles at us.’ It invites confrontation. Two-way communication and cooperation are what’s important. If one side overreacts, then it all falls apart.

We have bulked up America’s police. With DOD’s assistance, they developed units trained and equipped in military-style tactics. They demonstrate a consistent picture of organizations evolving from community-based law enforcement to security services whose primarily focus is maintaining public order. They see protests by minority or politically dissident elements as inherently illegitimate and potentially violent. The police can pretty much do whatever they want, to whomever they want, whenever they want. And it’s gonna be your fault.

Order, not justice is the new goal of our police, a significant shift in emphasis. As such, displays of overwhelming force are considered a logical way to prevent organized protests from happening. If demonstrations occur in spite of police presence, then massive use of force is a logical way to quell its impact and prevent its re-occurrence.

Many things demonstrate the evolution in America of police from “Protect and Serve” to a quasi-military force. This creates an emotional distance from the communities they patrol. We see this most clearly in their casual use of force, often disproportionate to the situation, and with a near-total lack of accountability.

That is an ugly symptom of our Republic’s weakness. The crushing of the Occupy Movement’s camps and the militarized response to the Ferguson protests are the natural outcome of our new policing.

When the country was founded, there were no organized police departments, and there wouldn’t be for about 50 years. Public order was maintained through private means, in worst cases by calling up the militia. The Founders were quite wary of standing armies and the threat they could pose to liberty, but they concluded (reluctantly) that the country needed an army for national defense.

They feared the idea of troops patrolling city streets — a justified fear colored by the antagonism between British troops and residents of Boston in the years leading up to the American Revolution.

The Founders couldn’t have envisioned police as they exist today. It is probably safe to say they’d be appalled at the idea of police, dressed and armed like soldiers, breaking into private homes in the middle of the night, as happens on drug busts on most nights in America. Using militarized police to roust demonstrators would likely be appalling to them as well.

Let’s close with Radley Balko:

We got here by way of a number of political decisions and policies passed over 40 years. There was never a single law or policy that militarized our police departments — so there was never really a public debate over whether this was a good or bad thing.

It’s time to have that debate.