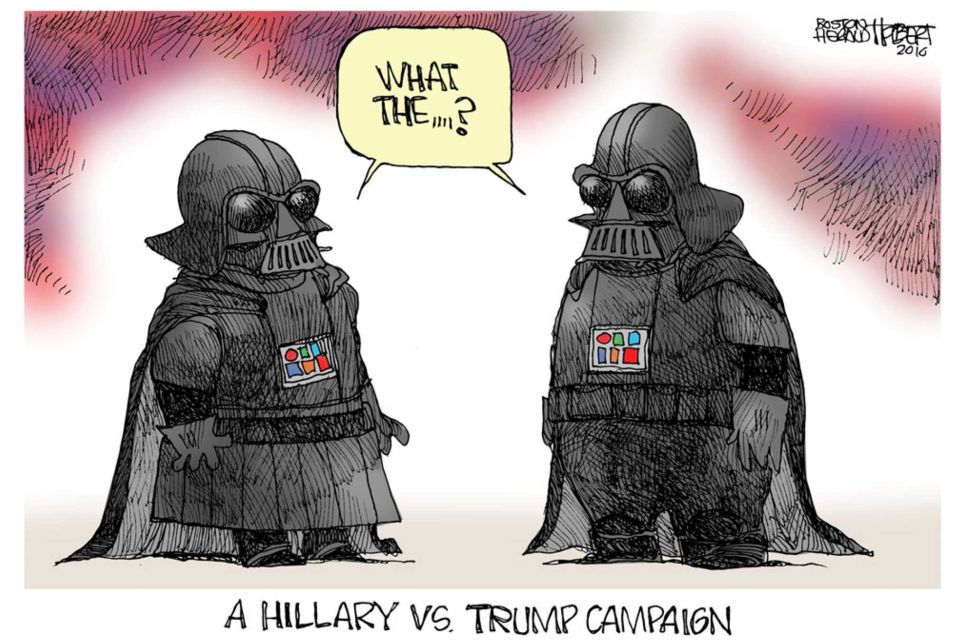

“The Past Is Never Dead, It Is Not Even Past” – Faulkner

Does this sound familiar?

They called for imprisonment of Americans who came from a foreign country. They called for shutting down immigration from certain countries and deporting the immigrants already here. They were for stifling dissent against a looming foreign war by calling the anti-war protestors traitors. They passed laws that curtailed several rights granted in the Bill of Rights.

An administration worked hard to “sell” a war to the American people.

This is not America in the post-9/11 period, it was during World War I, not during Iraq, or our current battle against ISIS.

And it occurred while a progressive Democrat was in the White House.

On April 6, 1917, Woodrow Wilson delivered his war message to Congress. The US, Wilson said, was to embark upon a crusade to “make the world safe for democracy“. Unfortunately, Wilson’s administration gave rise to the greatest attack upon civil liberties (up to that time) since the passage of the Sedition Act in 1798.

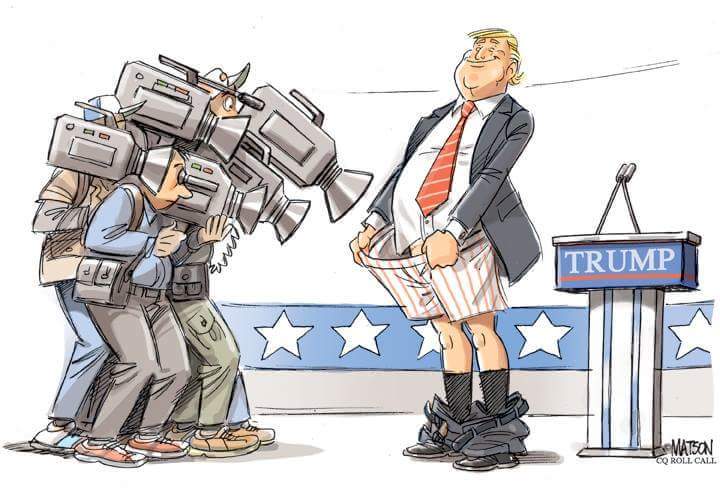

Wilson had two problems. First, the citizenry had to be mobilized behind a war effort that did not involve a direct attack on the US. Second, he felt a need to guarantee our internal security against both real and imagined enemies. To solve the first problem, in April, 1917, Wilson established the Committee on Public Information (CPI), under the leadership of George Creel, a respected progressive. The Committee’s job was to convince citizens that the war was righteous, and to educate all Americans about American war goals.

Writers turned out “true” stories concerning what the Germans planned to do to America; speakers toured the nation delivering anti-German talks. Movie audiences thrilled to “Pershing’s Crusaders” and came by the thousands to hate the enemy by watching dramas such as “The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin.”

Congress also enacted laws that curtailed our constitutionally guaranteed freedoms of speech and press. Shortly after Wilson’s war message, in June, 1917, the Espionage Act was passed. This made it a crime to make false reports which would aid the enemy, incite rebellion among the armed forces, or obstruct recruiting or the draft. In practice, it was used to stifle dissent and radical criticism.

In October, 1917, another law required foreign language newspapers to submit translations of all war-related stories or editorials before distribution to local readers.

In May, 1918, the Sedition Act bolstered the Espionage Act. It provided penalties of up to 20 years imprisonment for the willful writing, uttering, or publication of material abusing the government, showing contempt for the Constitution, or inciting others to resist the government. Under this Act, it was unnecessary to prove that the language in question had affected anyone or had produced injurious consequences. In addition, the Postmaster General was empowered to deny use of the mails to anyone who, in his opinion, used them to violate the Act.

In October 1918, Congress passed the Alien Act, by which any alien who, at any time after entering the US was found to have been a member of any anarchist organization, could be deported.

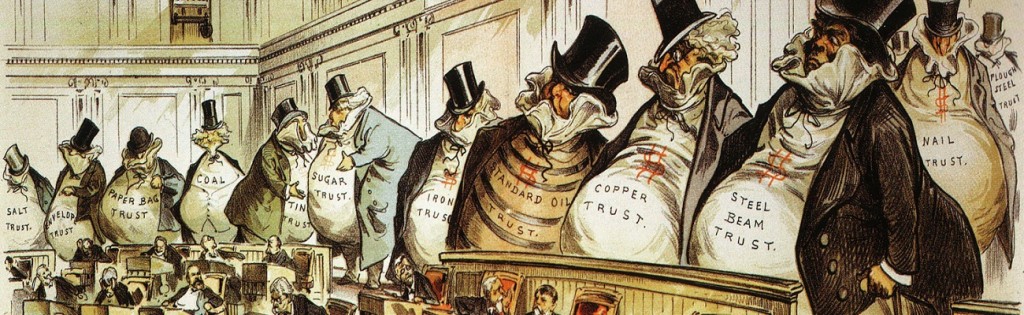

Volunteer organizations sprung up, dedicated to discovering alleged traitors, saboteurs, and slackers. The volunteer groups were hyper-patriotic, and were often responsible for violations of civil liberties, although the government made no real attempt to discourage or limit their activities.

With the quiet consent of the Department of Justice, the American Protective League’s 250,000 civilian members—many of whom wore official-looking badges reading “Secret Service”—undertook vigilante actions against supposedly disloyal socialists, pacifists, and immigrants; they engaged in domestic surveillance operations; and raided businesses, meeting halls, and private homes in an effort to uncover pro-German sympathizers. As a result, force became the order of the day.

Somewhere during the fight to make the world safe for democracy, Americans lost their tolerance, compassion and mercy, and much of their democratic ideals.

Does this sound familiar?

The various Acts of 1917 and 1918 helped destroy what remained of the left wing in America. Victor Berger, the first socialist elected to Congress, was sentenced to 20 years in prison for hindering the war effort. Eugene V. Debs was sentenced to 10 years in prison for making an anti-war speech.

On November 11, 1918, the Allies and Germany signed an armistice: the war was over.

The American public had shown a willingness to tolerate and even to participate in censorship, mugging, imprisoning, harassment, and forced deportation of Americans who didn’t agree with them.

Given where we are today, it could easily happen again.

Don’t bet against it.