A law professor at West Point was forced to resign after it emerged that he had authored a number of controversial articles. In one, he suggested that the US military may have a duty to seize control of the federal government if the federal government acted against the interest of the country.

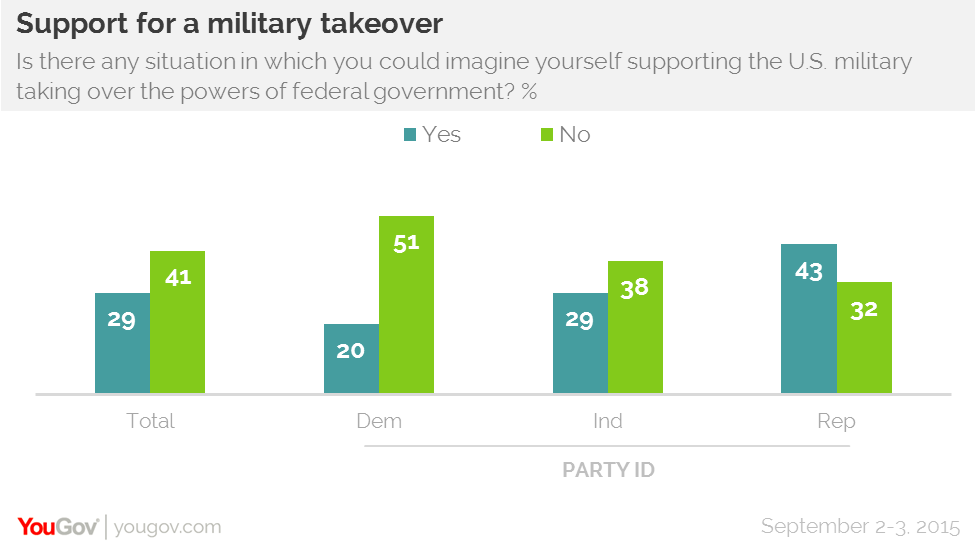

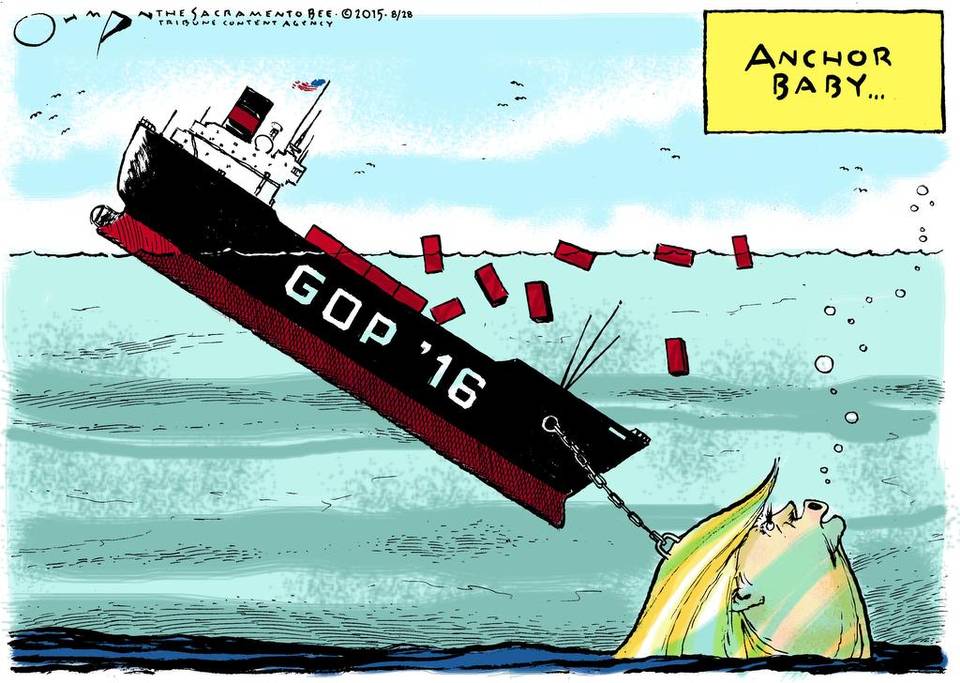

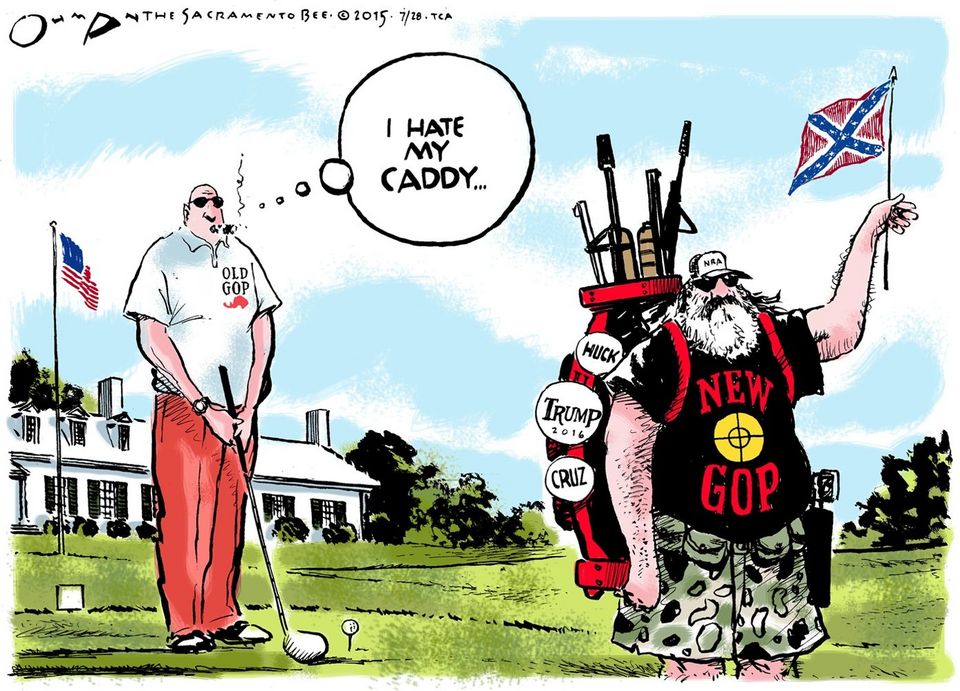

Link that thought to a YouGov poll taken this month that found that 29% of US citizens would support a military coup d’état. Moreover, a plurality of Republicans, (43%) would support a coup by the military. They were the only group with a plurality in favor in the poll:

They polled 1,000 people on September 2nd & 3rd. The poll has a margin of error of ±4%. Another theme of the poll was that Americans think the military want what’s best for the country, followed by police officers:

The other categories, which included Congress, local politicians, and civil servants, went in the other direction. The vast majority of those polled thought that local and DC politicians were self-serving.

In other words, most Americans have a lot of confidence in the police and the army, the armed enforcers of government’s rules, but very little confidence in the politicians and bureaucrats who actually write and enact them. This is a rather dangerous disconnect when you think about it. A fascinating poll question was: (emphasis by the Wrongologist)

5. Should active duty members of the US military always follow orders from their civilian superiors, even if they feel that those orders are unconstitutional?

Should . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .18%

Should not . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49%

Not sure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33%

The answer shows that many Americans think:

1. The military are all Constitutional scholars, and

2. Americans want soldiers to think for themselves, even though the civilian superior who matters is the Commander-In-Chief, or Mr. President to the rest of us.

All of this, despite the fact that the US military has long embraced the idea of civilian control of national affairs, and apart from certain rare moments, the American officer corps has faithfully followed the orders of their civilian superiors.

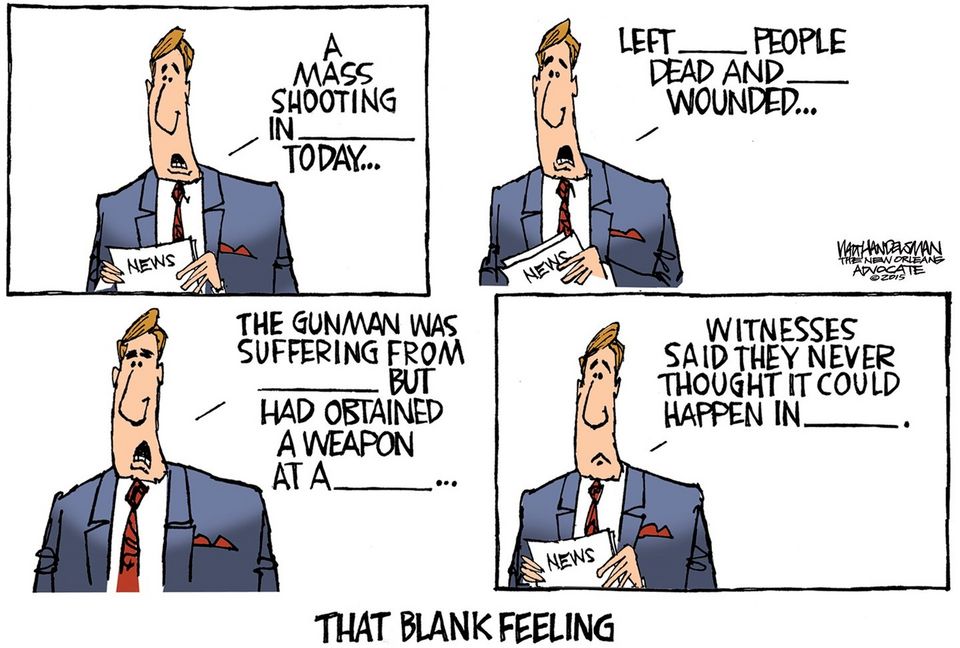

The weakening of support for many of our institutions is clear: Every year Gallup asks Americans about their confidence with 15 major segments of American society. The police and the military routinely top the list with overwhelming support, while no other government institution inspires confidence among the majority of voters. That includes the presidency, the Supreme Court, public schools, the justice system, and Congress. Also near the bottom, are the media, big business, and banks.

Essentially, the YouGov poll shows that most Americans have completely lost faith in the system, and the powers that run it. The only people they still trust are cops and soldiers. And a society that trusts its armed enforcers more than everyone else is a society that could be ripe for a coup. In today’s age of blanket surveillance, the military coup option may be especially appealing to quite a few US citizens who are afraid to risk their own lives opposing their government. It is a version of “let you and him fight”.

Those military officers who would make good political leaders are smart and too principled to launch a coup against the civilian government. We would likely see mass resignations of the officer corps before any attempted coup. So, a few questions:

• Why conduct this poll now?

• Who commissioned the poll, and why?

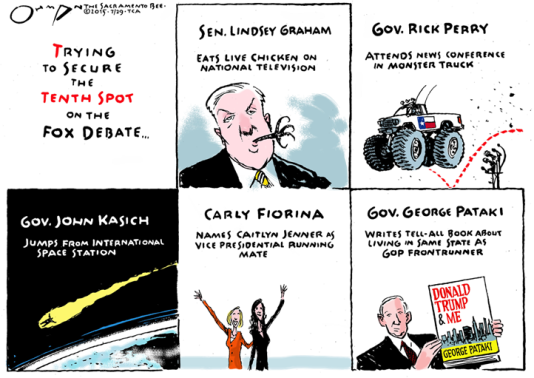

It’s clear that people are seriously disgusted with the political class. The first reasonably persuasive demagogue who comes along may give America’s political class exactly what it deserves.

Sadly, the rest of we Americans deserve better.