The Daily Escape:

Rich Mountain Fire Tower, Marshall, NC – August 2023 photo by Michael Morris. This photo has a painterly quality to it.

Americans’ interest in homeschooling has soared in recent years. Migrating from mainstream education to homeschooling tracks with the rising fears among parents that schools are failing their children.

For parents frustrated with their child’s public school education, the pandemic provided another reason to give homeschooling a try. Homeschooling has become a significant element in education in the US. According to the National Home Education Research Institute (NHERI), there are 3.7 million homeschooled students in the US, about 6.7% of the school-age children in K-12. The popularity of homeschooling is growing rapidly, with an annual growth rate of 10.1% between 2016 and 2021.

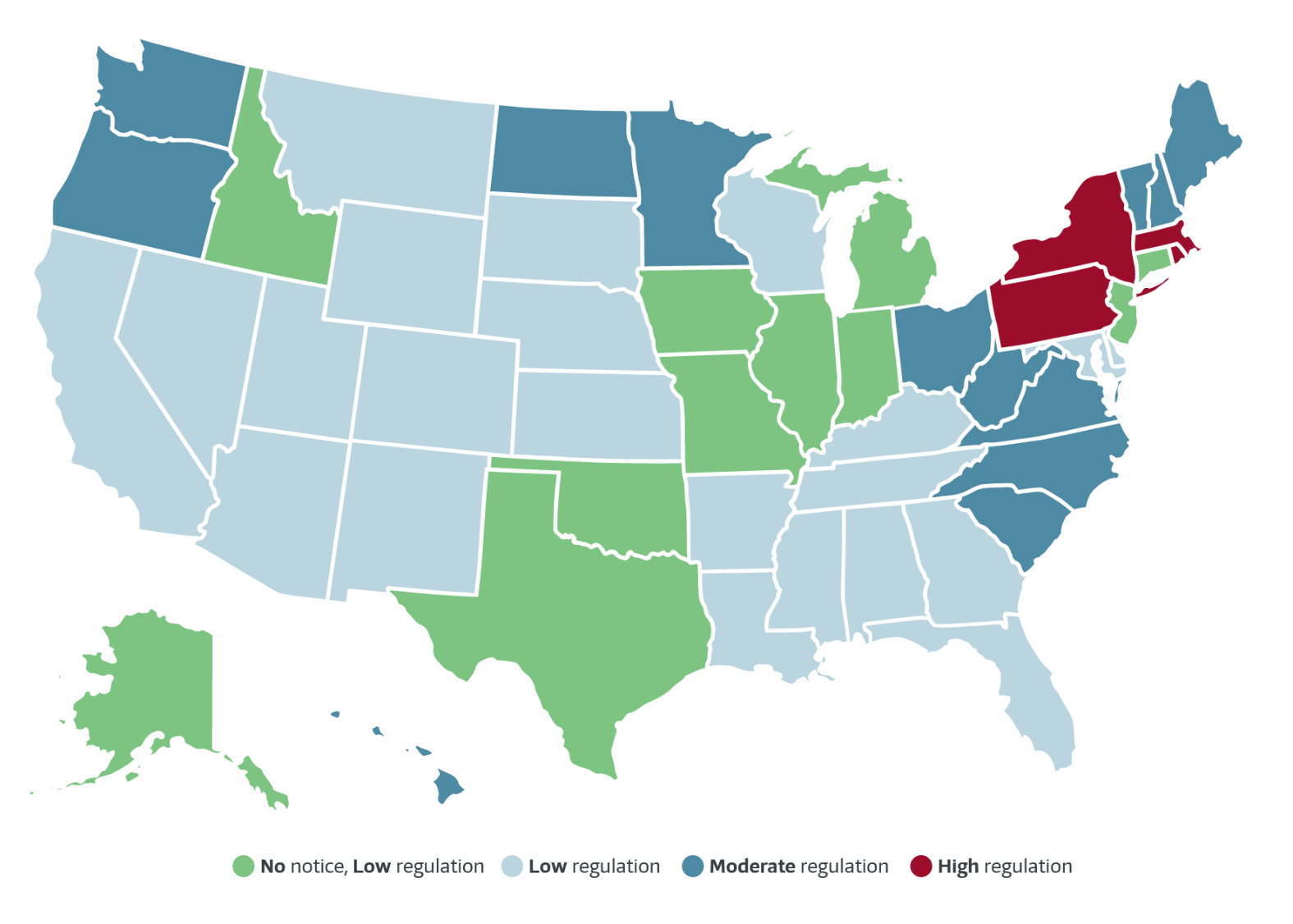

Home schooling is legal in all 50 states, with the highest number of homeschoolers in North Carolina, Florida, and Georgia. About 10% of states have strict laws regulating homeschooling: New York, Vermont, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania. Another 18 states have no to low regulation, while 11 states provide complete freedom to parents regarding homeschooling. In New Jersey, parents do not have to let anyone know about their decision to homeschool their children. They don’t even have to produce any kind of proof at any time, explaining that their kids were homeschooled. Here’s a view of homeschooling regulation in the US:

Source: HSLDA

In many states, there is little oversight of homeschooling. And for many, what regulations do exist were adopted in the 1980s, when homeschooling was almost exclusively provided by a family member at home. Now, with the number of homeschool students soaring, much of the educating is now being provided by third parties.

The WaPo reports that there is an emergence of “microschools” provided by for-profit companies, such as Prenda which provide online courses and syllabi to the microschools. Last year, Prenda served about 2,000 students across several states by connecting homeschool families with microschools that host students, often but not exclusively in homes. The local educator is called a “guide” for students who study math and reading online while depending on the “guide” for other subjects. Families pay Prenda $2,199 per year, plus additional fees set by the guides, which can range from $2,800 to $8,000 per child although there is often a multi-child discount.

Many similar options to Prenda are transforming home schooling in America. More from WaPo:

“Demand is surging: Hundreds of thousands of children have begun homeschooling in the last three years, an unprecedented spike that generated a huge new market. In New Hampshire, for instance, the number of homeschoolers doubled during the pandemic, and even today it remains 40% above pre-covid totals.”

More:

“For many years, homeschooling has conjured images of parents and children working together at the kitchen table. The new world of homeschooling often looks very different: pods, co-ops, microschools and hybrid schools, often outside the home, as well as real-time and recorded virtual instruction. For a growing number of students, education now exists somewhere on a continuum between school and home, in person and online, professional and amateur.”

Still more:

“Microschools sometimes provide all-day supervision, allowing parents to work full time while sending their children to “home school.” Hybrid schools let students split their days between school and home. Co-ops, once entirely parent run, might employ a professional educator.”

All of this is adding to the conundrum of how K-12 education is financed in the US. The WaPo says that about a dozen states allow families to use taxpayer funds for home-school expenses. Education Savings Accounts, or ESAs, direct thousands of dollars to families that opt out of public school, whether the destination is a private school or their own homes.

Nonprofits, including school-choice advocates, are directing millions of dollars in charitable giving toward homeschool organizations, linking two powerful but traditionally separate movements into one interest group that seeks to move taxpayer money away from the local public school system into private hands.

In the past, homeschoolers and school-choice activists didn’t see themselves as aligned. The latter group wanted taxpayer money to pay for charter, private and religious schools, whereas homeschoolers looked to limit any government involvement.

But since the pandemic, they found themselves in common cause. Historically, homeschool advocates have been wary of any government money or involvement, for fear it would lead to rules and regulations.

But many school-choice advocates incorporate support for homeschoolers into their advocacy work, including for school vouchers that give these families tax dollars to pay education costs. Where they used to be a defensive constituency, today they have become partners.

And venture capitalists have invested tens of millions of dollars in new businesses to serve what they see as a growing, and potentially huge market. One entrant is Outschool, an online marketplace for classes, which has raised $255 million since 2015. This year, Outschool has delivered 500,000 live learning sessions to more than 150,000 students globally.

WaPo says Prenda has raised about $45 million. Primer, another microschool company formed to serve homeschoolers, has raised about $19 million, though its campuses are becoming more like tiny private schools, an example of the fuzzy line between traditional and home schooling. WaPo spoke to Michael Moe, founder of GSV, a venture capital firm in the Silicon Valley, who has invested in several education technology start-ups: (brackets by Wrongo)

“The mega trend of [school] choice is wildly important to us…All these shifts create opportunities for companies providing solutions that allow parents and communities to take more control of the learning.”

That’s “venture capitalspeak” for more privatizing of the commons in search of higher financial returns.

Vouchers that once paid only for tuition at private and parochial school can now, in some places, be used for homeschoolers. Most sweeping are Education Savings Accounts, or ESAs, which allow families to claim state tax dollars to use at their own discretion for any education expense.

This increasingly means taxpayer money is following the student out of the public school. It flows to whatever a family chooses. That can include things like Prenda’s fees, online classes or home-school curriculum, as well as tuition at private schools.

In Detroit, a program called Engaged Detroit , is a cooperative that’s part of a network specifically to serve Black families looking for schooling options in response to the pandemic. Among Engaged Detroit’s backers is the VELA Education Fund, which has made more than 2,400 grants totaling more than $28 million since 2019. VELA’s primary funders are longtime advocates for school choice: the Walton Family Foundation and the Charles Koch foundation, Stand Together.

There are pluses and minuses to homeschooling. There are situations where it’s appropriate to homeschool, but the loose oversight and lack of expertise might mean that some homeschooled kids are going to be at risk. When parents say they don’t trust the trained/educated teachers in their public school, but instead want their kids to get the viewpoints of only one or two specific people, the kids are entering a small world. Later in life, they’ll have to adjust to a larger reality.

Wrongo is fully aware of the weaknesses of our public school systems. It’s possible that SOME of these small private schools that they say are “home schools”, are teaching those kids better than some public schools do. So Wrongo is ok if kids learn there. But there should be no problem with requiring these kids to take end-of-year minimum standards tests, proving that they learned the base-level material in each subject.

Without some testing, society has no idea if these kids learned anything. The lack of oversight, particularly in those situations where taxpayer money was diverted to homeschooling, seems well—Wrong.

The literature is clear: Some homeschooled children have attended Ivy League schools and won national spelling bees. Some have also been the victims of child abuse. Some are taught using the classics of ancient Greece, others with Nazi propaganda.

Many parents say home education empowers them to withdraw from schools that fail their children. Or they want to provide instruction that better reflects their personal values. But should the rest of us pay for those individual decisions?

Time to wake up America! Homeschooling may offer certain advantages, but also comes with a set of disadvantages that should also be considered. And it’s clear that those who would privatize K-12 education want to take funding from the public school systems wherever they can.

To help you wake up, listen to Steely Dan’s “My Old School” from their 1973 album “Countdown to Ecstasy”. Steely Dan always used outside musicians, and on the record, they had the late Skunk Baxter on guitar and four (!) saxophones. But Steely Dan didn’t like to tour. Today, we’re going to see a rare video of a Steely Dan live performance on “The Midnight Special” where Skunk had a blistering solo for the song’s finale: