The Daily Escape:

Waterfall Jumping Competition (from 69 feet up), Bosnia, August 5th – photo by Amel Emric

Every time I meet someone from outside Silicon Valley – a normy – I can think of 10 companies that are working madly to put that person out of a job…

Well, that makes most of us “normies”. In context, we are the people who do not work in Silicon Valley. We are the people who use technology, rather than invent technology, and many of us ought to see technology as a threat to our jobs and our place in society.

We are not in the beautiful peoples’ club. Our names are not on the list. We’re not software engineers who work just to pay the taxes on their company stock.

And who is this Martinez guy? From Mashable:

He’d sold his online ad company to Twitter for a small fortune, and was working as a senior exec at Facebook (an experience he wrote up in his best-selling book, Chaos Monkeys). But at some point in 2015, he looked into the not-too-distant future and saw a very bleak world, one that was nothing like the polished utopia of connectivity and total information promised by his colleagues.

Martinez pointed out that there are enough guns for every man, woman and child in this country, and they’re in the hands of people who would be hurt most by automation:

You don’t realize it but we’re in a race between technology and politics, and technologists are winning…

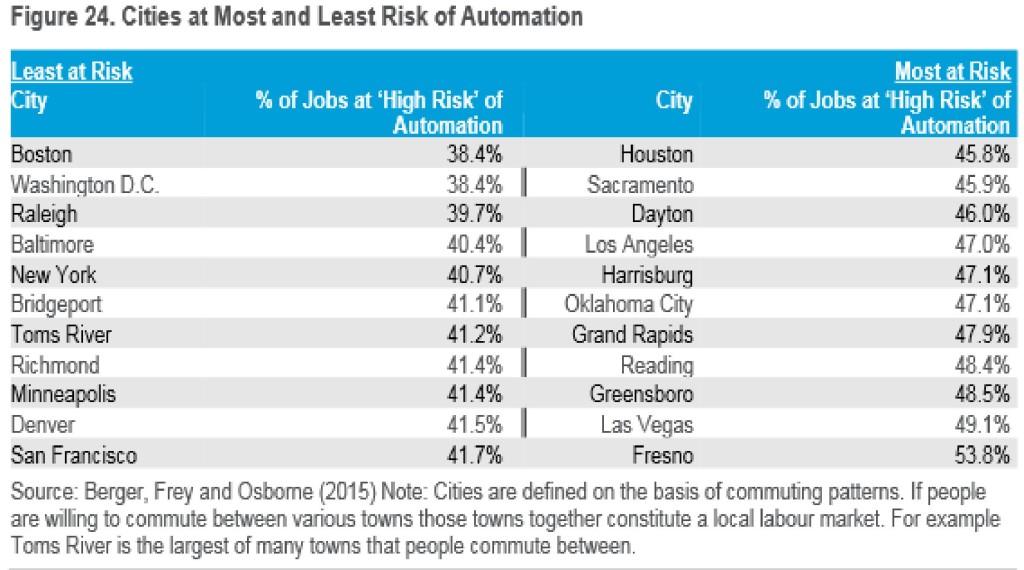

Martinez worries about how the combination of automation and artificial intelligence will develop faster than we expect, and that the consequences are lost jobs.

Martinez’s response was to become a tech prepper, another rich guy who buys an escape pod somewhere off the grid, where he thinks he will be safe from the revolution that he helped bring about. More from Mashable: (brackets by the Wrongologist)

So, just passing [after turning] 40, Antonio decided he needed some form of getaway, a place to escape if things turn sour. He now lives most of his life on a small Island called Orcas off the coast of Washington State, on five Walt Whitman acres that are only accessible by 4×4 via a bumpy dirt path that…cuts through densely packed trees.

He’s not alone. Reid Hoffman, co-founder of LinkedIn told The New Yorker earlier this year that around half of Silicon Valley billionaires have some degree of “apocalypse insurance.” Pay-Pal co-founder and venture capitalist Peter Thiel recently bought a 477-acre escape hatch in New Zealand, and became a Kiwi. Other techies are getting together on secret Facebook groups to discuss survivalist tactics.

We’ve got to expect that with AI and automation, our economy will change dramatically. We will see both economic and social disruption until we achieve some form of new equilibrium in 30 years or so.

It will be a world where either you work for the machines, or the machines work for you.

Robert Shiller, of the famous Case-Shiller Index, wrote in the NYT about the changing meaning of the “American Dream” from the 1930s where it meant:

…ideals rather than material goods, [where]…life should be better and richer and fuller for every man, with opportunity for each according to his ability or achievement…It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of a social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable…

That dream has left the building, replaced by this:

Forbes Magazine started what it calls the “American Dream Index.” It is based on seven statistical measures of material prosperity: bankruptcies, building permits, entrepreneurship, goods-producing employment, labor participation rate, layoffs and unemployment claims. This kind of characterization is commonplace today, and very different from the original spirit of the American dream.

How will the “Normies” survive in a society that doesn’t care if you have a job? That refuses to provide a safety net precisely when it celebrates the progress of technology that costs jobs?

The Silicon Valley survivalists understand that, when this happens, people will look for scapegoats. And we just might decide that the techies are it.

Today’s music is “Guest List” by the Eels from the 1996 album “Beautiful Freak”:

Takeaway Lyric:

Are you one of the beautiful people

Is my name on the list

Wanna be one of the beautiful people

Wanna feel like I’m missed

Are you one of the beautiful people

Am I on the wrong track

Sometimes it feels like I’m made of eggshell

And it feels like I’m gonna crack

Those who read the Wrongologist in email can view the video here.