The Daily Escape:

Sun, clouds and Saguaros, North Scottsdale AZ – photo by rayredstonemedia61

After three decades of digital technology development, it’s evident that cybersecurity isn’t being adequately ensured by Mr. Market’s “invisible hand.” In remarks at the White House last Thursday, Biden said:

“…private entities are in charge of their own cybersecurity…and we know what they need. They need greater private-sector investment in cybersecurity.”

Wrongo’s last assignment was as CEO for a division of a F500 defense contractor. We were targeted by Chinese and other hackers thousands of times per day. By 2005, the parent company was investing tens of millions annually on cybersecurity. Most non-defense firms have come to investing in cybersecurity slowly and without large funding.

We again became painfully aware of the issue when hackers shut down the Colonial pipeline on Mother’s Day, bringing back gas shortages and long conga lines of cars trying to fill up. We subsequently heard that Colonial paid the hackers $4.4 million in Bitcoin to regain control of their networks.

From the New Yorker:

“…we are a country that has seen nearly a thousand reported ransomware attacks on our critical infrastructure since 2013. This includes transportation services, wastewater facilities, communications systems, and hospitals. The average recovery cost of a ransomware attack for businesses is around two million dollars.”

Even though private companies are most vulnerable to counterattacks, they continue to set their own cybersecurity standards largely based on operational and economic priorities, even if their negligence exposes the public to risks. So why won’t companies fix their mess?

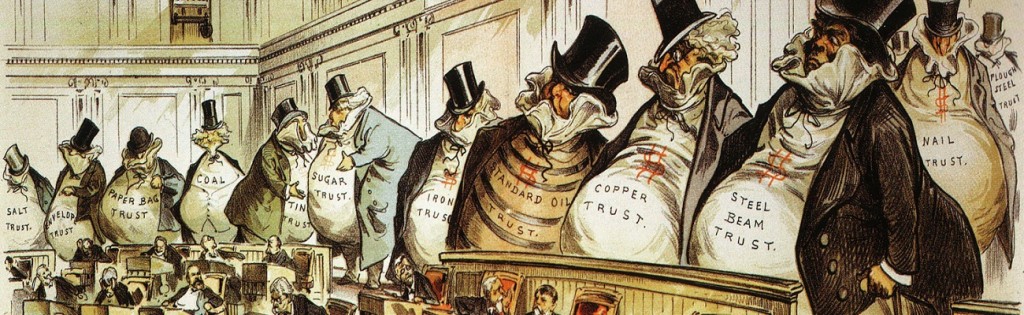

Most in the private sector think that cybersecurity regulations will cost too much, which they do not want to pay, or may be incapable of paying. Many in the private sector also consider requirements for better cybersecurity to be yet another form of government regulation.

Mostly, it’s about money and secondarily, about a shortage of IT skills. Some argue that the incentive structure is backwards. Companies often think the costs of adding robust cybersecurity to be higher than their likely losses from a cyber theft. In a way, they are self-insuring, but that ignores the harm to their customers that occurs when personal information is stolen, or when you can’t buy gasoline.

CEOs are concerned primarily with the short-term profits and stock prices of their corporations. Companies have regularly absorbed losses incurred by security breaches, rather than reveal weaknesses in their internal cybersecurity systems, all in the name of protecting management reputations.

In 2015, Obama’s DHS designated dams, defense, agriculture, health care, and twelve other sectors of the economy as “critical infrastructure,” meaning that they:

“…are so vital to the US that their incapacity or destruction would have a debilitating impact on our physical or economic security or public health or safety.”

But while the DHS issued cybersecurity guidelines to those sectors, most companies operating critical infrastructure (like Colonial) are privately owned, and they ignored them. That includes 80% of the energy sector, including pipelines, power generation, and the electricity grid. DHS said in 2015 that those industries needed to develop a common vision and framework to deal with cyber threats.

But corporate America never developed that vision and framework.

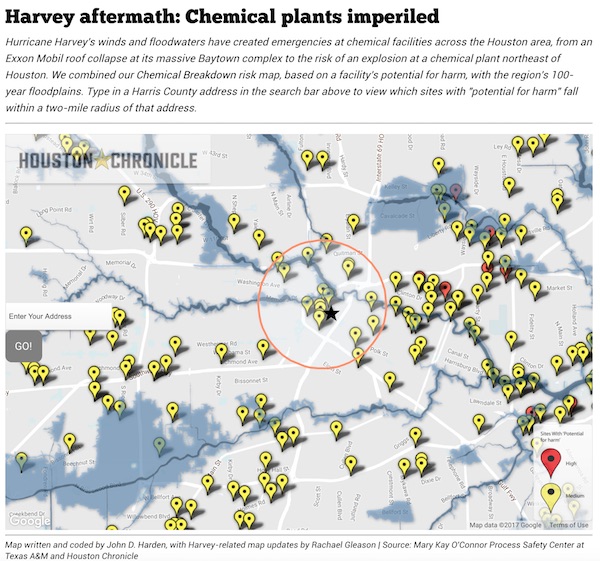

In 2019, a European cybersecurity researcher using open-source tools available to anyone, identified and mapped the location of twenty-six thousand industrial-control systems across the US whose internet configurations left them exposed and vulnerable to attack. But you know, they would be prohibitively expensive to fix.

On May 12th, Biden issued an executive order that directed federal agencies and their contractors to abide by a host of stringent new cybersecurity regulations and reporting requirements. The order also required IT service providers and companies that operate industrial-control systems, to inform the government about cybersecurity breaches that could affect American networks.

Biden’s order is a significant workaround for the lack of government control of cybersecurity in the private sector. Many of the cloud services and software packages used by government agencies are also used in the private sector. So, Biden is creating the likelihood that those standards and requirements will be more broadly adopted. That would be similar to auto-emissions standards: When California raised its standards, 12 other states decided to adopt those requirements, and five automakers agreed to design all their new cars to meet them.

Something similar could occur with cybersecurity. Like with Covid, we’re again learning that there’s a very good reason for a robust central government that has the will to write and enforce 21st Century regulations.

Time to wake up America! Corporations aren’t your friends. From sending jobs abroad, to out-of-control share buybacks, to failing to invest in cybersecurity, they need much closer scrutiny. To help you wake up, let’s dust off Depeche Mode with their 1989 hit “Personal Jesus”: