The Daily Escape:

Saguaros and poppies, Catalina SP, Tucson, AZ – March 2024 photo by Paul J Van Helden

From Jeff Asher, a crime analyst based in New Orleans:

“Murder plummeted in the United States in 2023, likely at one of the fastest rates of decline ever recorded. What’s more, every type of Uniform Crime Report Part I crime with the exception of auto theft is likely down a considerable amount this year relative to last year according to newly reported data through September from the FBI.”

We all knew that crime rates skyrocketed between the mid-1960s and the late 1980s. Then they went into a slow 35-year decline. Now, homicide, violent crime, and property crime rates have returned to what they were prior to the latest 20-year increase. This means that if you’re under 55, crime rates have been falling for most of your adult life.

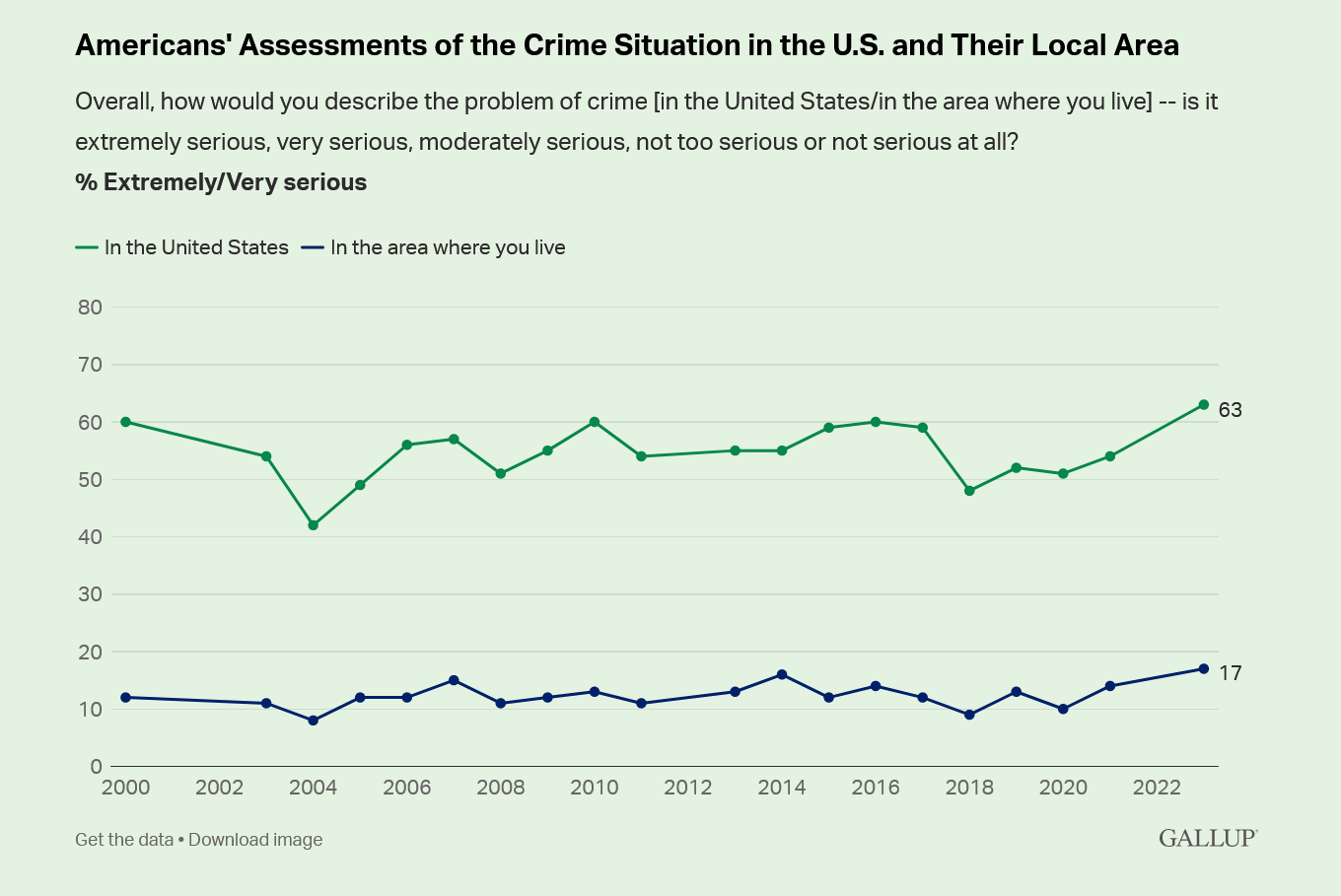

But America perceives that crime rates are high. A Gallup poll released last November found 77% of Americans believed there was more crime in America than the year before. And 63% felt there was either a “very” or “extremely” serious crime problem — the highest in the poll’s history going back to 2000.

Wrongo doesn’t truly believe the polls since Pew revealed that 12% of people under 30 and 24% of Hispanic people who opt into online polls claim they have a license to operate a nuclear submarine, but here’s a chart:

(This is based on Gallup’s annual Crime survey, conducted Oct. 2023)

The question is, why the disconnect? NPR quoted Jeff Asher:

“There’s never been a news story that said, ‘There were no robberies yesterday, nobody really shoplifted at Walgreens….Especially with murder, there’s no doubt that it is falling at [a] really fast pace right now.’”

One theory you might have is that since the Covid pandemic caused social disorder, dysfunction in our government, and all sorts of problems, including that spike in crime, you might expect crime to remain high even after the country went back to work and school.

Another theory is that when people say “crime“, they don’t exclusively mean “people breaking the law“. Instead maybe they mean “behavior which upsets me“. For example, when the Philadelphia DA tries to focus on eliminating bail for simple drug arrests, while opposing police corruption, he’s said to be soft on crime. Then Republicans (and Trump) tried to impeach him, saying that they’re being “tough on crime” and crime remains a politicized news story.

Another theory is that the narrative around homeless people drives perception of crime. The idea that “homeless people have been violent“, or simply that “homeless people live near me and I don’t want any shelters built nearby,” strengthens the perception that crime is everywhere. For people who feel that way, the statement “Crime is a big problem” is equivalent to the statement “I always see homeless people when I go into town”.

This may explain why crime rates “near me” are perceived to be substantially lower than how national crime is perceived. Few of the homeless are encamped in their suburbs.

If you look back on the 1980s, there were a large number of visible homeless people in Washington DC, and Reagan dismissed them as “homeless by choice“. Today, there are plenty of homeless people on the streets in every city. It’s important to remember that when St. Reagan was governor of California, he released mental patients onto the streets.

This was part of “deinstitutionalization”: The emptying of state psychiatric hospitals that began in the 1950s. As hospitals were shut down, patients were discharged with no place to get psychiatric care. They ended up on the streets, some eventually committing crimes that got them arrested.

In 1963, JFK signed the Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Health Centers Construction Act. (It turned out to be the last bill Kennedy would sign.) The law was designed to replace “custodial mental institutions” with community mental health centers, thus allowing patients to live—and get psychiatric care—in their communities.

However, a sufficient number of community mental health centers were never built.

In 1965, Medicaid accelerated the shift from inpatient to outpatient care: One key part of the Medicaid legislation stipulated that the federal government would not pay for inpatient care in psychiatric hospitals. This further pushed states to move patients out of their state facilities.

That’s when homeless people began to be visible to most of us.

Later, in the 1970s, Nixon declared a war on drugs, setting the stage for tough-on-crime policies. Laws, like mandatory minimum sentences for possession and other drug-related crimes, disproportionately affected people of color and pushed incarceration rates to record levels. Between 1972 and 2009, America’s prison population grew by 700%.

The homeless get blamed for the bad behavior of a small minority of their group. But since an awful lot of the dysfunctional are homeless because their families or friends couldn’t cope with their behavior, it’s logical that the general public would also find their behavior a problem.

And it’s more than just the homeless. In Wrongo’s small Connecticut town, long-time residents resent people who have moved in recently. They are appalled by the occasional drug arrest or stolen car that was left unlocked in a driveway.

This scales up to people in our town bellowing about CHICAGO!!!! Or LA or Portland, OR. They see the far enemy as young Black/Hispanic men in certain zip codes destroying each other. And just possibly turning their attention to our tight, white community here in the Litchfield Hills.

It’s a good thing that overall crime and especially violent crime rates are much lower than they were 30 years ago. But we’re still faced with the overriding perception that people see their families at greater risk now.

This has spilled over into how parents treat their children. NO parent today would allow their kids to get on a bike and roam miles from home. Everything is monitored. If you ask why, the near-universal response is: “It just isn’t safe out there. Not like it used to be.”

Used to be? Most kids were tooling around on their bikes Goonies-style during the 1980s, when crime nationwide was at its peak.

People just seem hell bent on seeing the world as a massively scary place, one filled with predators.

There are major political implications, when data aren’t facts, when truths are lies.